The Birth of Football and the Origins of Manchester City

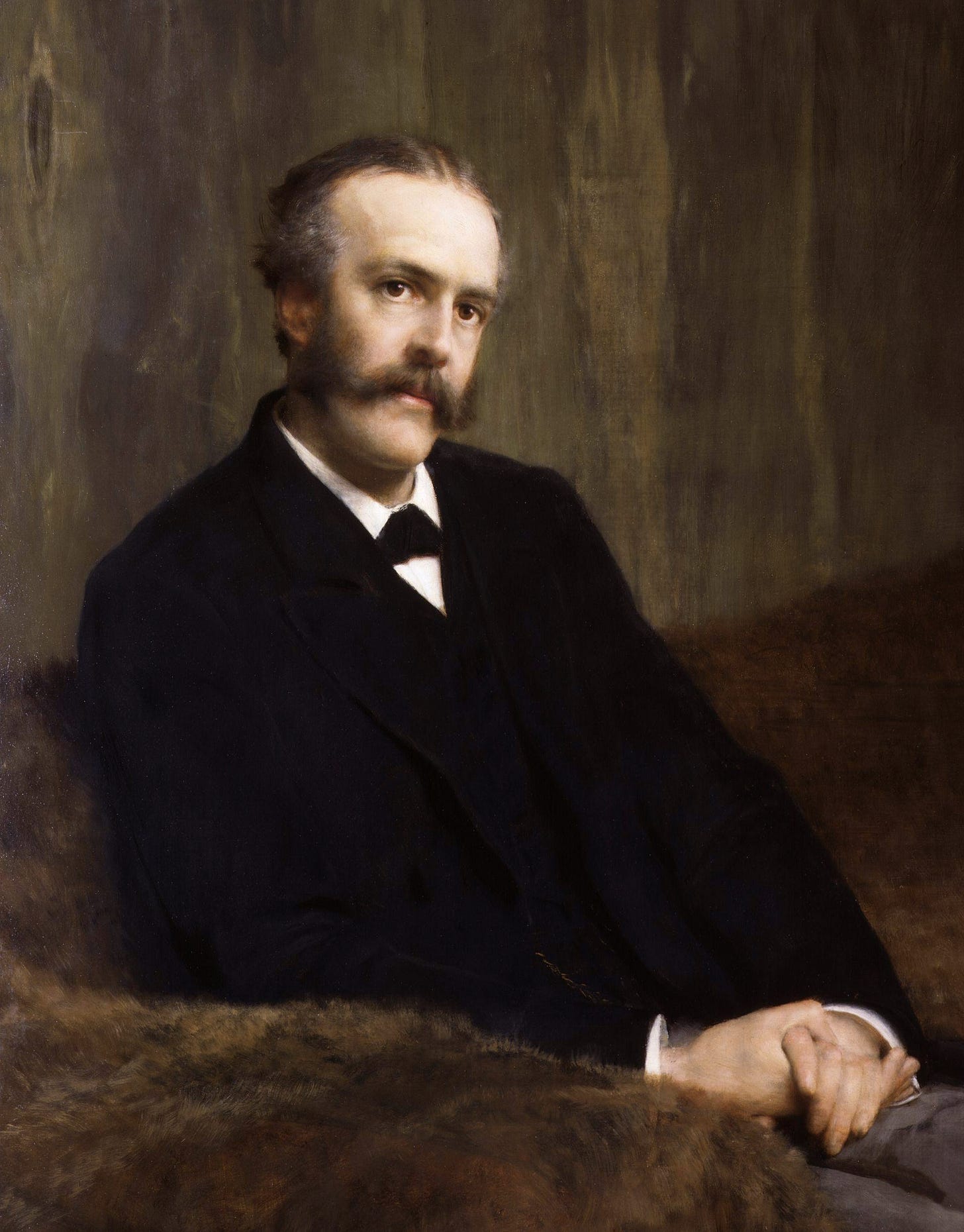

Twenty: Success To Balfour

In July 1891 Stephen Chesters Thompson organised a challenge shield competition of 48 schools, including four Catholic ones. After the event it was reported that he had

'generously offered to purchase a piece of land, if such could be obtained, for the use of the boys in Ardwick for recreative purposes, irrespective of creed.'

It was an uncharacteristic display of ecumenicalism from the Ardwick AFC president, a Church of England warden who had previously campagined to cut funding to Catholic schools.

But Ardwick’s financial benefactor was first and foremost a politician.

Four months earlier he had become an alderman, and the Conservatives’ ‘de facto group leader’ in the City Council. But it was his role as chairman of election committee for Manchester East MP Arthur Balfour that was now dominating his thoughts.

They were “an ill-assorted pair”, Manchester-based judge Edward Parry once called them. The aristocratic Eton-educated Balfour was known for his intellectualism and aloofness. In contrast, the outspoken and passionate Chesters Thompson was dubbed the “high priest of poetry, romance and melodrama”. And he was never more passionate than in his support for Balfour. In his autobiography, Parry recalled one incident that came at the end of a Conservative Party meeting in Ardwick. Patting Balfour endearingly on the shoulder ‘with a heavy paw’, Chesters Thompson declared:

“I luve (sic) Arthur James Balfour. And I tell you boys this, that should the day ever coom (sic) that it is necessary, I shall be there to place the body of Stephen Chesters Thompson between Arthur James Balfour and the dagger of the arsarsin (sic).”

The threat of assassination was real. Balfour’s brutal suppression of a rent strike as Secretary for Ireland in 1887 had sparked outrage among Manchester’s sizable Irish community, and resulted in the Manchester East MP keeping his public appearances in the city to a minimum.

With the upcoming General Election expected to be tight, it was Chesters Thompson’s job to repair Balfour’s reputation. And the newly rebuilt Hyde Road ground would be central to his strategy.

A year earlier Ardwick AFC had hosted its first athletics festival there, attracting a 6,000 crowd. For the final race, the Four Mile Scratch, Balfour had presented a 'handsome £25 silver cup' to the winner, worth around £23,000 in today's money.

And now it was time for Ardwick’s footballers to be put to the Tory cause. On 3 August 1891, Athletic News announced,

‘The Ardwick Club has managed to reconstruct its committee somewhat without the aid of a general meeting, and Mr. R. Stevenson is now chairman, and a capital one he will now make, for he is a thoroughly business-like gentleman. He will have the assistance of Mr Allison, who has decided to continue on the committee, although he resigned the chairmanship. Mr R. Leach is again the treasurer, and is one of the best men I know to look after the money bags of a football club.’

The report added,

‘And, in addition, they have an admirable and generous president in Alderman Chesters-Thompson, who has always proved himself willing to assist the club in every way. Several gentlemen have guaranteed large amounts if they are required.’

The changes meant that Ardwick were now under the complete control of Chesters Brewery. Richard Leach was the brewery’s treasurer while new club chairman, Richard Stevenson, was its company secretary (Stevenson was the landlord of the Hyde Road Hotel when Chesters Thompson made him secretary in 1888, a surprise appointment that may have been influenced by the pair being members of the same Masonic lodge).

Allison’s resignation as chairman was most likely due to political pressures. In October he nominated Liberal candidate Henry Matthews in the council election for the Ardwick ward. His Conservative opponent, William Fitzgerald, was nominated by Chesters Thompson and Leach.

On 4 October the growing Tory influence over Manchester football was on display when Ardwick travelled to Newton Heath in the qualifying round of the FA Cup. The match was kicked off by the Conservative MP for Manchester North East, and Postmaster General, Sir James Fegusson, while his Liberal opponent, Manchester Guardian editor C. P. Scott, watched on from the stands.

Ardwick lost the game 5-1, which was played in front of a 12,000 North Road crowd. The following Saturday Ardwick returned for an Alliance league match and suffered a 3-1 defeat. Now falling behind in the battle for Manchester football supremacy, the gulf that remained between Ardwick and football’s top tier was illustrated on 10 February, when Ardwick entered the Lancashire Senior Cup for the first time and lost 6-0 to League members Accrington.

The Manchester Senior Cup was now Ardwick’s only chance of silverware, though the Manchester FA’s decision to extend its boundaries to include Bolton presented a formidable obstacle.

A 3-1 defeat to Fairfield in the semi-final on 12 March appeared to end Ardwick’s chances of retaining the trophy. But following the game Ardwick lodged a protest, claiming a Fairfield player named Roberts had appeared in a junior cup tie for Stretford so was ineligible.

Umpire News questioned whether any such rule existed, claiming that the Manchester District FA’s ‘own code of rules shows no clearness on the point’. The Fairfield secretary denied that Roberts had played for them that day, while the player’s foreman claimed Roberts was working on the afternoon he was supposed to have played for Stretford. Despite that, a replay was ordered, which Ardwick won 4-0.

It unclear whether political forces played a part in these shenanigans, though the fact that Balfour was now the second most powerful politician in the land after being appointed First Lord of the Treasury and Leader of the House of Commons in October, probably didn’t hinder Ardwick’s case.

On 23 April Ardwick met Bolton Wanderers in the final at North Road. Few gave them a chance against a full-strength Bolton, who had just finished third in the League. But Ardwick did have the highest-earning player in the land, forward and captain David Weir (the 1891 census reveals that Weir employed a live-in servant at the home Chesters Brewery had provided for him).

With the score tied at 1-1 at half time, early in the second half,

‘Weir, getting the ball at the centre, evaded all his opponents, and beat Sutcliffe with a beautiful shot, which was greeted with loud and prolonged cheering.’

A second goal from Weir sealed a shock 4-1 win. Ardwick’s superior fitness levels, aided by special training in Matlock under the guidance of John Allison, also played a key role in the victory. According to The Umpire:

‘Ardwick, though, certainly had the best of matters during this (second) half, playing against the wind with surprising energy.’

On 6 May, Chesters Thompson presented Weir with the trophy at the Spread Eagle Hotel in Manchester. It was an exclusively Conservative affair. Also present were William Fitzgerald, now the councillor for the Adwick ward, and Edward Tatton, Tory councillor in the St Luke's ward. Chesters landlord and Conservative activist Thomas Cairns, and Chesters company secretary, Stevenson, were also present. Allison, who had drunk beer from the trophy during the 1891 presentation, was not invited.

The following day Balfour made a rare visit to his constituency. Chesters Thompson (described by Umpire News as ‘the sole proprietor of the district’) met him at Ardwick station before presiding over a rally in the ballroom at Belle Vue Zoological Gardens. As ‘the music of the “Conquering Hero” reverberated around the hall’, Balfour addressed his constituents for the first time since 1887.

A week later Ardwick were elected to the newly-formed Second Division of the Football League, after the Alliance was integrated into the League. Chesters Thompson’s spending spree had paid off. And now it was time to reap the political dividends.

On the day of the General Election on 6 July, Ardwick AFC’s headquarters, the Hyde Road Hotel, was charging 1d for pints of beer (the normal price was 2½ to 4½d) to customers who used the phrase “Success to Balfour”. Several brewery employees were given the day off in order to help Balfour, while free lemonade shandies—dubbed "smilers"—were handed out throughout the constituency.

That day Balfour beat Liberal candidate Joseph Munro by 398 votes, with a swing to his rival that was only half the national average. But Balfour’s Conservative Party lost 79 seats in the election, allowing Gladstone’s Liberals to return to government.

Manchester’s liberal establishment was now on the offensive—and Chesters Thompson was its no.1 target.

My book on City’s origins, A Man’s Game, is available on Amazon here.

What was the first song at City? Why did Steve Coppell resign? Did City have a “Fifth Column”? Did the IRA try to burn down Hyde Road? Who started the “banana craze”? And what was Maine Road's Scoreboard End called before there was a scoreboard?

All these questions—and more—are answered in my latest book, available on Amazon here.

You can subscribe for free, below, and have the latest stories sent straight to your inbox.

Extremely interesting reading , how strange it is really to think that Manchester was such a conservative stronghold back then when for as far as I can remember it’s always been a city dominated by labour politicians! Looking forward to reading the next chapter