The Birth of Football and the Origins of Manchester City

Part Five: The Primordial Soup

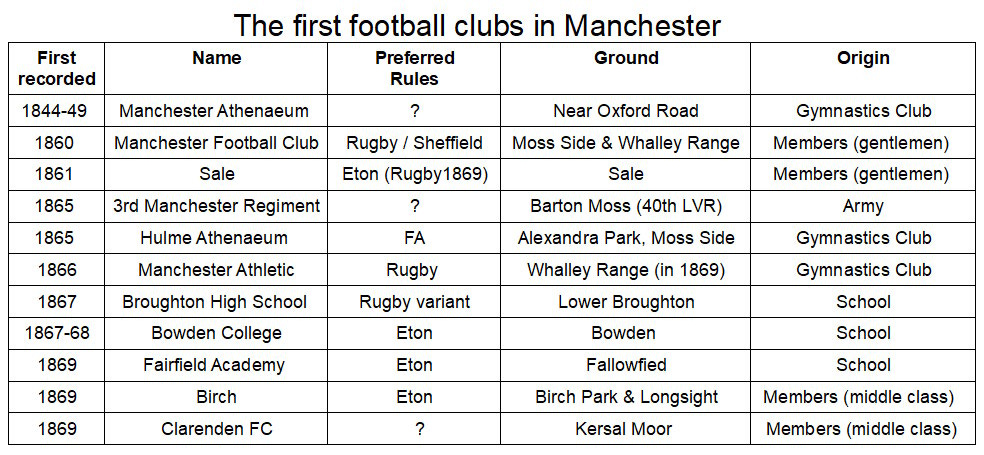

By the end of the 1860s Manchester boasted at least eleven football clubs. Originating from self-improvement societies, elite schools, or created by their middle or upper-class members, they had finally established football as a respectable pastime in the city.

However, one major barrier lay in the path of further expansion: no one could agree what rules to play.

At this time there was a wide variety of codes called football, virtually all of which allowed some form of handling. Disagreements centred around whether you could throw, catch or run with the ball, the method of scoring, and the legality of kicking or tripping an opponent.

At least six of Manchester's clubs, including Hulme Athenaeum and Sale, appear to have favoured the Eton game, the only code to prohibit use of hands except for catching. The 15-a-side game awarded three points for goals scored into a 12ft by 6ft “citadel”, and one point for a rouge (where the ball crosses a goal line within a flag placed to the side of the posts). The ball, which could not be passed forward, spent most of the time out of sight in a violent scrimmage called a “bully”. which was won by kicking the ball into touch.

Manchester FC tried Rugby, Sheffield and Harrow rules, while the game played by the remaining clubs is unclear. The number of football codes was still multiplying during this period, as some clubs picked their own combinations of public school rules. For instance, in 1863 the Lincoln Football Club was playing a code that was “drawn from” Marlborough, Eton and Rugby rules. Referees were not used, on account of gentlemen not needing them, so whether players adhered to any official code during the heat of competition is a matter of debate. Rules were often agreed before each game, sometimes during, and occasionally not at all. A match between Sheffield and Newark in December 1869, for instance, was “played to no particular rules”.

Practically no one was playing London Association rules. At the FA's annual meeting in 1866 it was claimed that only three clubs in the country were following them, all in London.

However, the FA was driven by an idea: to create a unified code for the United Kingdom. And as no one seemed to like their rules, they decided to change them. In March 1866 the London FA adopted two important Cambridge Rules (also used by Charterhouse and Westminster schools) for the first ever “representative” match, played at Battersea against a combined side from Sheffield, a footballing hotbed that boasted around 13 clubs.

A maximum height was placed on the goal and a three-man offside rule was introduced, which spread out play and made passing easier. Two years later the Sheffield Association made several rule changes that brought the two codes closer together, abolishing rouges and permitting fair catches. In January 1871 Sheffield made a more radical rule change, becoming the first code to prohibit both catching and handling the ball. The rule became a cornerstone of the association game, enabled the passing game, introduced the goalkeeper, and allowed the new technique of heading.

Sheffield’s new code proved popular in other other regions, posing a threat to the new FA Cup competition, created in July 1871 as football’s first national knock-out tournament. So in November 1871 the Sheffield and London FAs arranged two trial games between the associations. The first, played in Sheffield under London rules, illustrated how much the FA were still wedded to the rugby-like game. At one point FA secretary Charles Alcock picked up an opponent and threw him to the ground, a tactic that did not seem to warrant a free-kick.

The return match the following month, played under Sheffield Rules, resulted in another clash of football cultures. The London eleven did not include a goalkeeper, which was still unnecessary as all players were allowed to handle the ball, and invited Sheffield FA President J C Shaw to play in goal for them.

The sight of Sheffield players heading the ball ‘caused some amusement’ among the sparse London crowd, while the Sheffield Telegraph deplored London's disregard for throw-ins, noting that

‘the spectators generally stopped the ball at the boundary, handing it to whichever player came up first.’

However, further games over the next two seasons led to the rules merging closer, while international matches between England and Scotland introduced the modern-day throw-in. By the 1873-74 season the number of FA Cup entrants increased from 15 to 28, while a Sheffield versus London game attracted a crowd of 5,000 ‘of whom a great number were ladies’ on the new terracing at Bramall Lane. Sheffield won the game 8-2, with one local newspaper contrasting the “very scientific and strategic disposition” of the Sheffield players to the more physical approach of the London players.

One side that certainly wasn't short on strategy was the Royal Engineers Football Club. It was armed with a spirit of innovation that, in 1916, saw them take German trenches in the first day of the Somme without suffering a single casualty. Under its founder, 34-year-old Crimean war veteran Captain Francis Marindin, they had reached the inaugural FA Cup final in 1872 and the following season won 19 of their 20 games, scoring 73 goals and conceding just 2.

In October 1873 they demonstrated mastery of both London and Sheffield codes by beating Sheffield 4-0 using a new 2-2-6 “combination” formation, so called because it combined dribbling with passing. Sheffield also ran into a rock-like Engineers defence that at times saw all 11 players in the goal mouth (which may be the earliest example of a team “parking the bus”).

The Engineers' success showed London the superiority of the combination game. Following Marindin's appointment as FA president in 1874 further rule changes, including a minimum playing area and a “kick-in”, enhanced the passing game and brought the two codes closer. By March 1875 the last remaining area of dispute was between Sheffield's one man offside rule and London's three. “Why not split the difference and make it two?” one Sheffield delegate suggested. That particular idea would not be implemented until 1925, and other characteristics of the modern game, such as penalty kicks and the 18-yard box, would not be introduced for some time.

But the foundations of a nationwide association football code had now been laid.

You can subscribe for free, below, and have the latest stories sent straight to your inbox.

Part Five

Very interesting read as always . I wonder why Sheffield in particular was such a hotbed for “ soccer “ when most other large cities seemed to embrace a rugby style version of football ?