The Birth of Football and the Origins of Manchester City

Seventeen: Play up, Ardwick

On 17 September 1887 the renamed Ardwick AFC played Hooley Hill in their first game at their new Hyde Road home.

They'd been scheduled to play there a week earlier, and according to an early history of the club, had hired a band for the occasion. A crowd of around 500 had turned up. Unfortunately, their opponents, Salford AFC, didn’t and the match was cancelled.

There was no fanfare for the Hooley Hill game, however, which finished in a 4-2 defeat for Ardwick. But the the 'delightful weather' had at least encouraged a 'fair number of spectators' to watch the team of Gortonians that had adopted their district's name.

The 4½-acre Hyde Road enclosure bore little sign that it would become the home of future FA Cup winners. There were no stands, and the badly sloping pitch would soon turn inhto a mudbath thanks to the land's severe drainage problems.

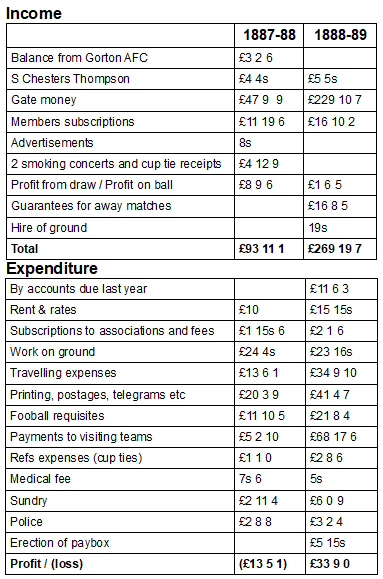

But there were two notable firsts that season that signalled a change in footballing culture. The season's accounts reveal that the club received income from advertising for the first time, though the name of City's first-ever sponsor, who paid the club eight shillings, has been lost to history.

The 1887-88 season also saw the first recorded incident of hooliganism at a City match, which probably explains a payment for policing that appeared in the accounts. It came at the end of a 1-0 defeat away to Edenfield on 26 November when fans reportedly ‘stoned the visitors off the field’. Newspapers also contain the first accounts of a noisy travelling away support, for the 3-2 defeat away to Lower Hurst in the first round of the Manchester Cup on 21 January. According to one report, Lower Hurst's first goal was

'much to the chagrin of the Ardwick spectators who seemed to be tearing their throats with with shouts of “Play up, Ardwick”.

The report also noted that the “Ardwickians” 'cheered for their team very lustily' after pulling the game back to 3-2.

But there wasn’t a great deal else to cheer that season, with the club finishing with a modest record of P34 W14 D7 L13 F91 A80. According to the first written history of the club in an 1898 edition of the Golden Penny magazine:

‘Subscriptions were modest, and the early gates of this amateur team were as small as the present ones are large. There was the same difficulty in amateur clubs then as there is now, and it was often no easy matter to whip up an eleven, while it was impossible to play the same men together every Saturday. In fact, it was often a question of inducing outsiders to aid the club to fulfil some of the fixtures.’

The waterlogged Hyde Road ground was also posing problems. In February Ardwick were forced to replay the second round Ashton Charity Cup tie against Hyde after the Hyde Road pitch was ruled unfit for football.

But the new enclosure was at least producing financial rewards. An average crowd of around 340 that season produced £47 9s 9d in gate money, a more than 20-fold increase on the 1885-86 season (no accounts have been found for the 1886-87 season).

However, the gap between the established clubs and the fledgling ones such as Ardwick was now about to get bigger.

On 17 April 1888 the Football League was formed at a meeting at the Royal Hotel on Mosley Street, situated less than two miles from Hyde Road. On 8 September the first League games were played. Four of the matches were watched by an average crowd of close to 4,000. The other game, Everton v Accrington at Anfield, attracted a 12,000 crowd.

But the move to Hyde Road represented more than a change of location for the club. Ardwick was one of the great entrepreneurial hubs of Manchester. And one local businessman, 35-year-old hydropathic baths proprietor John Allison, was eager to tap into the district’s footballing potential.

On 1 September he had arranged match at Hyde Road against Matlock with a £10 guarantee, and soon afterwards joined the club’s committee. Derbyshire-born Allison had arrived in Ardwick in 1887, opening a business offering pioneering forms of pain relief with water treatment on Hyde Road. It was the start of an 18-year association with the club that culminated in Allison becoming City chairman in 1906 (see this story).

In the 1888-89 season Allison provided funds for players, as did another committee member, local public house owner, John Chapman. Working side by side for now, the two men were to later represent two opposing factions—the sporting pioneers and the drinks trade—that would dominate the club’s politics for the next 30 years.

Their involvement appears to have produced instant results. Following the 3-3 draw with Matlock, Ardwick went on a run of eight successive wins, prompting one newspaper to declare that

'Ardwick had every prospect of developing into a first rate club.'

But it was Allison’s next door neighbour, brewer Stephen Chesters Thompson, who recognised the club’s potential more than anyone. As managing director of the giant Chesters Brewery, he used company funds to pay for a 1,000 capacity wooden stand, increasing Hyde Road’s capacity to 3,000 (the ground’s first turnstile was also installed that season).

Ardwick was now a club on the rise.

On 2 February a record Hyde Road crowd of 3,000 watched them defeat local rivals Gorton Villa 7-0 in the second round of the Manchester Cup. But the potential for Manchester football was best illustrated eleven days later when an Ardwick & District side that contained six Ardwick AFC players took part in a charity match against Newton Heath for the Hyde Colliery Explosion Fund. Played under floodlights at Belle Vue, the 12,000 crowd was by far the largest ever seen at a football match in the city.

On 16 March Newton Heath, now the city’s premier club, once again knocked Ardwick out of Manchester Cup, winning 4-1 at North Road. Although Ardwick ended the season with a much improved record of P43 W32 D5 L6 F167 A69, they were still a world away from the country’s elite clubs.

However, thanks to Chesters Thompson, that was all about to change.

My book on City’s origins, A Man’s Game, is available on Amazon here.

What was the first song at City? Why did Steve Coppell resign? Did City have a “Fifth Column”? Did the IRA try to burn down Hyde Road? Who started the “banana craze”? And what was Maine Road's Scoreboard End called before there was a scoreboard?

All these questions—and more—are answered in my latest book, available on Amazon here.

You can subscribe for free, below, and have the latest stories sent straight to your inbox.

Excellent reading