The Birth of Football and the Origins of Manchester City

Part One: What Is Football?

The subject of football’s origins has prompted much debate over the years—and precious little agreement.

Some have dated it to first century China, where a game called tsu chu (meaning “kick ball”) was played. Similar games, typically played by children, have been found in many other cultures, including ancient Greece and North America, where a game called pasuckuakohowog (meaning “the gather to play ball with the foot”) was played by some native tribes.

The first record of “a game of ball” being played in Britain was in the 9th century. Around the 1170s William FitzStephen's A Description of London provided the first detailed account of the game, which was played on a public holiday called “Carnival”. After spending the morning watching cock-fighting with their teachers “all the youths of the city goes out into the fields for the very popular game of ball.” FitzStephen continues,

“The scholars of each school have their own ball, and almost all the workers of each trade have theirs also in their hands. The elders, the fathers, and the men of wealth come on horseback to view the contests of their juniors, and in their fashion sport with the young men; and there seems to be aroused in these elders a stirring of natural heat by viewing so much activity and by participation in the joys of unrestrained youth.”

For the next few hundred years the game appears to have served largely as an outlet for local rivalries, played mainly on public holidays. According to James Walvin's The People's Game, medieval football was an ‘ill-defined contest between indeterminate crowds of youth, often played in riotous fashion’. Reports of violence and damage to property during matches were numerous, injuries were common and deaths not unheard of. The problems associated with the playing of football led to more than 30 royal and local prohibitions being introduced across the country between 1324 and 1667. One such ban was introduced in Manchester in 1608, when the Manchester Leet court noted that

‘There hath been heretofore great disorder in our towne of Manchester, and the inhabitants thereof greatly wronged and charged with makinge and amendinge of their glasse windows broken yearelye and spoyled by a companye of lewd and disordered persons using that unlawfull exercise of playinge with the ffote-ball in ye streets’.

The Manchester Leet court imposed a hefty fine of 1s 2d for anyone caught playing football, and appointed six officers to enforce the ban. Puritans, unhappy that the sport was being played on Sundays, also hindered its growth. But it was probably the 18th-century enclosures—which saw vast areas of common land transferred into private ownership—that most hindered the game, particularly as in rural matches the goals could be three miles or more apart.

One place it was free to flourish was the public school. The first reference to public school football was at Eton in 1519 where a game was played “with a ball full of wynde”. According to Walvin, early public school football “closely resembled the popular folk game” though in a smaller playing area and with fewer participants. The game spread to other public schools in the early 19th century at a time when they were plagued by violent disorder (a riot at Rugby school in 1797 was put down by the army and one of Winchester school's many riots was quelled by the militia). But in the 1830s and 1840s the idea of “Muscular” Christianity—which linked physical fitness to spirituality and good morals—took hold in public schools. And under the watchful gaze of educationalists the rules of the game began to be codified.

After the first set of rules were created at Eton in 1815, other public schools devised their own codes. This caused confusion when the schoolboys reached university so in 1848 Cambridge University drew up its set of rules, which appear to be based on the Eton game. But this did not solve the problem of competing codes. The Sheffield Rules, created in 1858, became popular in the north, and in 1862 were joined by two new sets of rules: a revised version of Rugby Rules, which became the basis of rugby football, and Uppingham Rules, created by the co-author of the 1848 Cambridge rules, E J Thring. Even individual clubs had their own set of rules. For instance, in 1863 the Lincoln Football Club was playing a code that was “drawn from” Marlborough, Eton and Rugby rules.

So in October 1863 representatives of Eton, Westminster, Harrow, Winchester and Rugby schools announced they were to form a club—called the “Miserable Shinners”—“in order to arrange one general set of rules for football”. They failed in their task, but succeeded in creating the Football Association, which adopted its first set of rules on 26 October 1863.

Although these are now viewed as the first rules of the modern-day game of association football, a closer examination shows they were anything but.

Goals were scored by kicking the ball at any height between two poles, usually from a free-kick awarded for touching the ball down past the goal-line. A “fair catch” (where a player makes a mark with his heel) earned a free-kick, and throw-ins were similar to rugby line-outs. For goal kicks, opposition players had to stand behind their own goal-line, meaning a lot of play would consist of two packs charging at each other. And with no player permitted to be between any opponent and the goal when the ball was played to him, forward passes were limited to high punts up the field.

Charging at an opponent head-first, jumping on them and kneeing them was also permitted under the 1863 rules. Oh, and there were no goalkeepers either.

All of which makes it pretty clear that the first rules of the Football Association were not the first rules of what we now call association football.

So when did the game start?

To answer that question we first have to ask another: “what exactly is football?”

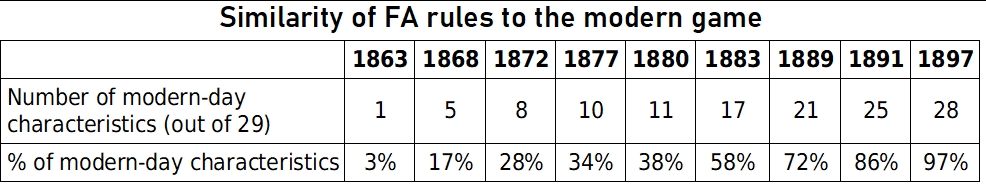

I’ve been studying the evolution of the FA’s rules from 1863 to the end of the 19th century. My starting point was to identify 29 characteristics of the modern game (this is not an exact science, by the way, so others might come up with a different number), then plot how many of those characteristics were found in each successive set of rules.

I’ll be going into a lot more detail about this later in the serialization, but as you can see from the results below, it wasn’t until the creation of the International FA Board in 1883 (the body that is still responsible for the rules of football) that the rules had more in common with the modern-day game than differences.

And it is the evolution of these rules from the late 1870s to early 1890s—and the reasons for it—that will be the focus of this serialization.

It is the story of a brutal game, which became a beautiful one.

You can subscribe for free, below, and have the latest stories sent straight to your inbox.

Looking forward to the rest of it ! At least something decent came out of public schools then !