The Birth of Football and the Origins of Manchester City

Sixteen: The Journey To Hyde Road

On 20 July 1885, after years of squabbling and threats, the Football Association finally lifted its ban on professionalism.

Thirteen days earlier an announcement had appeared in Athletic News:

‘The Gorton Association Football Club, who possess a good enclosed ground, are anxious to arrange matches.’

Gorton’s new ground was on land behind the Bull's Head public house on Reddish Lane. It was the only public house close to the giant Reddish iron works, guaranteeing brisk trade on half-day Saturday afternoons. And as entry to the ground could only be obtained through the pub, a boisterous crowd was also a near-certainty.

It was precisely the type of football that the FA, an organisation run by temperance campaigners, had been trying so hard to suppress.

For the time being, however, the fledgling Gorton AFC were out of the sights of football’s London overlords.

In fact, Gorton were barely making a ripple in the footballing backwaters of Manchester.

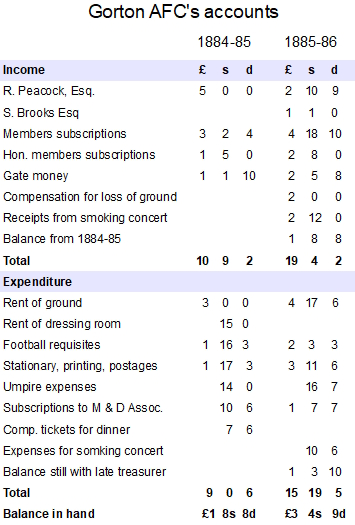

They were once again knocked out in the first round of the Manchester Cup after losing 2-1 away to Pendelton Olympic in December, and finished the season with a record of P13 W6 D3 L4 F30 A19 (1884-85: P16 W7 D2 L7 F31 A21). Although the gate money increased from £1 1s 10d to £2 5s 8d that season, the club were barely attracting 60 paying spectators per match.

In stark contrast, the footballing giants of the Lancashire mill towns were taking the game to new heights, with clubs from the Midlands in hot pursuit. In April 1886 Blackburn Rovers won their third successive FA Cup after beating West Bromwich Albion in a replay. It was the first final to be contested by working-class sides, and the last time an upper class side reached the later stages of the competition.

But Manchester is a not a city that gets left behind.

As the city’s ever-growing number of fledgling clubs battled for local supremacy, the more ambitious of them now realised that Manchester’s 400,000 population offered enormous potential for growth.

In September 1886, Athletic News noted that

‘The Association Code seems to be making great headway in Gorton, as there are no fewer than six clubs in the district.’

Those clubs were: Gorton Association, Gorton Ramblers, Gorton Rovers, Gorton Villa, West Gorton, West Gorton Athletic and West Gorton Hibernians. And in the 1886-87 season one of them, Gorton AFC, decided to make its move.

On 22 January 1887 Gorton finally won a Manchester Cup tie after beating West Gorton Athletic 5-1 in the first round. More importantly, the ‘rough and noisy’ game attracted 1,000 paying spectators. That generated receipts of nearly £13, three times the total gate money for the previous two seasons.

A match report for the game noted that the Gorton side contained ‘both bigger and older players’ than their opponents. And it was this age advantage that perhaps was the key to their next move.

Attendances in other first round ties had increased significantly from the previous season. The West Manchester vs Denton game attracted a crowd of 4,000, Newton Heath’s tie with Hooley Hill drew a 2,000 attendance, and Gorton Villa vs Oldham Olympic 1,500.

Gorton AFC’s committee realised that their ground was now holding them back. The absense of terracing limited capacity to around 1,000 (the number of fans who could stand two-deep around the touchlines), while its location near Gorton's sparsely-populated eastern border with Reddish also limited potential growth.

The club needed a better venue, one with good railway links and the potential for an enclosed ground. And planning was already underway.

Four days earlier club secretary Walter Chew had written to the agent of Manchester, Sheffield & Lincolnshire Railway company:

'The committee of Gorton Association FC are anxious to make arrangements with you to rent the ground situate between Galloway's works and Bennett's yard, Ardwick.'

The following month Gorton played Newton Heath in the second round of the Manchester Cup They lost 11-1, but the fact that their opponents were able to attract a 3,000 crowd to their enclosed ground in Clayton would not have been lost on the Gorton men.

On 17 August 1887 Gorton’s four committeemen (future City chairman Lawrence Furniss, brothers Walter and William Chew and William Mayson) signed a seven-month tenancy with the MSLR for their land on Hyde Road. It cost them £10, compared to the £4 17 6d they'd been paying for the Bulls Head ground.

Two weeks later, a meeting of club members and the public was held at the Hyde Road Hotel. At the meeting, organiser Walter Chew announced that the club had adopted the name of the local district.

Their new home was a 4½-acre patch of waste ground, sandwiched between a timber yard and a boiler works. Situated in the heart of Ardwick and closed off by the railway lines of the LNWR and MSLR, it was ideally suited for the creation of a large, enclosed ground.

With Manchester football now primed for explosive growth, the young men from St Mark's had just bagged the best spot in the city.

My book on City’s origins, A Man’s Game, is available on Amazon here.

What was the first song at City? Why did Steve Coppell resign? Did City have a “Fifth Column”? Did the IRA try to burn down Hyde Road? Who started the “banana craze”? And what was Maine Road's Scoreboard End called before there was a scoreboard?

All these questions—and more—are answered in my latest book, available on Amazon here.

You can subscribe for free, below, and have the latest stories sent straight to your inbox.

Check out this excellent Man City Newsletter - https://open.substack.com/pub/boysinblue?r=295m4&utm_medium=ios