The Birth of Football and the Origins of Manchester City

Part Ten: The First Season (1880-81)

St Mark's inaugural football match, against Macclesfield Baptist on 13 November 1880, would have been unrecognisable from the modern-day game.

The pitch had no touchlines (it would be three years before they're introduced). The playing area (which could be a maximum 200x100 yards under FA rules) would have been marked out by four corner flags, while a tape attached to the goalposts formed a crossbar of unknown height.

The style of play would have been even less recognisable. None of the players would have dared to turn their backs to goal. As jumping at or on opponents, kneeing them and “charging” them head-first were all allowed under FA rules, that would have almost certainly resulted in them being flattened to the ground. Scrimmages—similar to a rugby scrum—were a common aspect of the match. One lasted over five minutes and towards the end of the match it was reported that 'scrimmages became the order of the day'.

In fact, a 21st century time-traveller that happened to attend the game would probably assume they were watching a variant of rugby. Which is precisely what Manchester association football still was. A good example of the similarity of the two codes in Manchester had been provided in May 1880, when Manchester Wanderers took on rugby side Cheetham in an end-of-season exhibition game. The first half was played under rugby rules, while Wanderers failed to score in the second half that was played under association rules. Indeed, a newspaper reported noted that several Cheetham players were ‘adept’ at association play.

However, although both codes allowed for a remarkable degree of violence this does not appear to be a characteristic of the Baptist match, with a match report describing it as a 'very pleasant game'. This is most likely down to the influence of the church, which was also present in St Mark's second game (and association's first-ever Manchester derby) against Manchester Arcadians at Belle Vue on 27 November.

Arcadians, which had been founded by non-conformist minister Norman Glass, were described in a match report as being 'somewhat deficient in combined play'. In contrast, St Mark's 'played very well together, evidently the result of considerable practice'. This suggests that the St Mark's players might have been playing matches outside of the church team.

Unfortunately, the amount of football played in West Gorton at this time will be forever shrouded in mystery. The only reason match reports exist for St Mark's games is that pretty much every church activity was recorded in local newspapers. If other games were being played outside of the church, they would not have been deemed worthy of newspaper coverage.

It does seem likely that employees of the district's many iron works were playing some form of football at this time on their half-day Saturdays. Union Iron, where many of the St Mark's players worked, employed 700-900 men. However, although sporting activity is known to have taken place on a spot of land just to the west of the iron works called Farmer's Field, the details of the exact sports played remain sketchy.

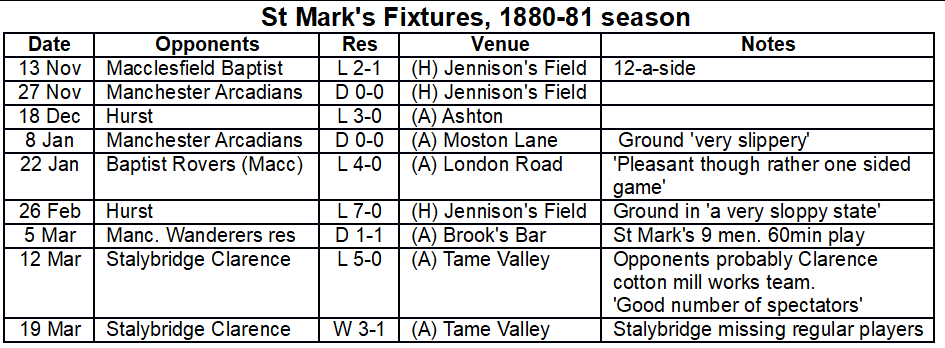

So we are left with just ten recorded St Mark's games for the 1880-81 season.

There was little glory to be found in that first season. St Mark’s lost five and drew three of their first eight games between November and March, scoring just two goals and conceding 22.

The lowest point of the season was a 7-0 defeat at home to Hurst on 26 February, a bruising encounter in which the ‘very sloppy state’ of the ground caused ‘very numerous’ falls. A match report described the Hurst forwards as ‘working together like machinery’ that day, an indication of the rugby-like characteristics of the Manchester game.

The more cultured football played in the mill towns of Lancashire was yet to impact Cottonopolis. That style of football was still a little too hot to handle.

The only Manchester side to have entered the Lancashire Cup in the 1879-80 season, Manchester Wanderers, lost 11-0 at Darwen in the 4th round and didn’t enter again. In fact, after a ‘decisive defeat’ at Blackburn Rovers on 25 October 1880, in which Wanderers captain scored three consecutive own-goals and his side ‘were completely in the hands of their opponents’ from the kick-off, they avoided mill town sides altogether. Newton Heath only played two games against a Lancashire mill town side that season, losing 6-0 on both occasions to Bolton Wanderers reserves. It would be three years before they dared take on a mill town side again.

But the association game had finally established a foothold in the city.

Despite a difficult first season St Mark’s at least ended on a high, winning their final game away to Stalybridge Clarence on 19 March. It was not the only reason for optimism. A week earlier a ‘good number of spectators’ had watched the two sides play.

Although still firmly in the shadows of rugby, interest was now growing in the “dribbling” game. The following season would see two more Manchester clubs created. And one of them would be St Mark’s first local rival.

You can subscribe for free, below, and have the latest stories sent straight to your inbox.

My book on City’s origins, A Man’s Game, is available on Amazon here.

Another excellent piece , the “scrimmages “ must have been some spectacle to see . Puts the likes of Declan Rice and his two yellows (leading to a red card yesterday )into perspective.