The Birth of Football and the Origins of Manchester City

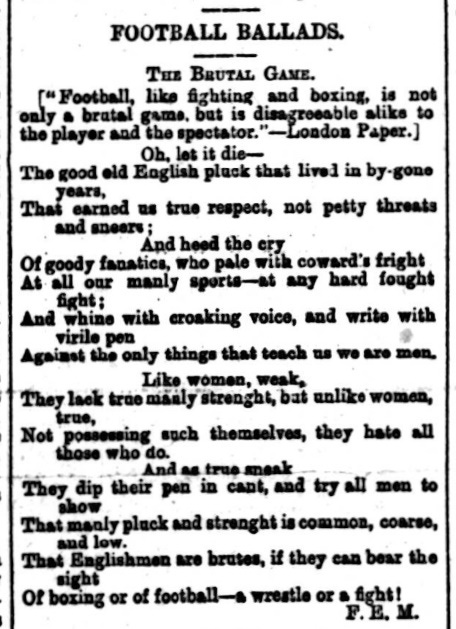

Part Six: The Brutal Game

By the mid-1870s rugby had established itself as the dominant code in Manchester. The creation of the Rugby Football Union in 1871 had boosted the popularity of the game nationwide, ensuring that rugby was the adopted code of the Manchester District Association on its formation in 1872.

By 1875 there were around 30 clubs in the district, including at least half a dozen church teams. None of them were playing under FA rules.

But in October 1875 former Nottingham Forest footballer and athlete, Fitzroy Norris, wrote to Athletic News calling for the formation of an association club for Manchester. It was a revival of the idea of an athletics football club, with Norris stressing the 'real good' that association 'afforded running men during the slack season’. A month later, the Manchester Association Football Club was formed at a public meeting organised by Norris and former Nottinghamshire footballer Stewart Smith. They were joined by John Nall and Charles Pickering, two influential figures from the first Manchester club to play under FA rules, Hulme Athenaeum.

On 13 November a side selected by Nall played one chosen by fellow honorary secretary Smith ‘on land adjoining’ Pepperhill Farm in Moss Side. The match took place at a time of intense debate on the merits of the two codes, one centered on their relative dangers. Three months later that debate took on a deadly tone.

In the early hours of 6 February 1876 Joseph Ison, a 16-year-old music seller's assistant from Moss Side, died from injuries sustained in a rugby match the previous day. His team, Egerton, were playing Fallowfield Rovers at Chorlton. It was a fixture that had previously resulted in bad blood (in March 1875 Egerton abandoned a home match against Fallowfield following a disputed goal), and Ison's injuries were the result of an illegal “charge” by a Fallowfield player. At the inquest two days later coroner Mr F Price condemned the “brutish” aspect of the game and warned that further cases could result in manslaughter charges.

Rugby was getting a bad press elsewhere in the country. In March the Sheffield Daily Telegraph declared that the game 'consists principally of protracted scrimmages, garotting, legging, tripping and tearing of clothing etc'. In Manchester, Ison's death sparked calls for the sport to be banned, or certainly discouraged, and resulted in the Egerton club being disbanded. It also prompted a sports enthusiast calling himself “Nyren” (probably after renowned cricketer John Nyren) to write to the Manchester Courier and claim that if clubs adopted Manchester Association's code

'we would hear less about the rough game of football, and there would be less chance of accidents; skill and speed would take the place of strength'.

He called this ‘true football’, though also spoke of the merits of Rugby Union, whilst playing down its dangers. That prompted a furious response six days later. 'It is not until one is called to a grave of a friend who has met his untimely death by this evil that the reality of such folly appears in its full magnitude', “CWV” wrote. Condemning Rugby Union as 'most barbarous and disgusting', he noted that 'on the day of the Ison accident in games played near Manchester another player had his leg broken, a third had his shoulder dislocated and a forth received such a “butt” in the stomach as to seriously hurt him’. Expressing interest in the new association club, he concluded that its code, unlike rugby, was ‘condusive to physical health’.

“Nyren's” response that it would be cowardly 'to shirk a game because there is a spice of danger in it' probably expressed the views of most rugby enthusiasts. One rugby club, Broughton Wasps, was prepared to play the fledgling club under FA rules that month, as was Levenshulme in April. But there was still little enthusiam in Manchester for the “London” game.

Indeed, it’s unclear how committed Manchester Association were to the evolving FA rules. In November they tried out the Sheffield Rules at Stoke and the Eton-inspired rules of Rossall School at Fleetwood. In a match against Sheffield the following month they appeared unable to deal with Sheffield's tactic of crossing (called “wonderful screws from side”) and heading. Manchester lost the match 4-0. However, the Sheffield Daily Telegraph was optimistic about the city's prospects:

‘With fine weather and good matches, there is no reason why association football should not in time be as popular and well supported in Manchester, as it now is in Glasgow and Sheffield. The time may or may not be far distant, but eventually the brutal rough Rugby rules will give way before the more artistic and superior game adopted by the association.’

But the return fixture at Bramall Lane on in February 1877, played under Sheffield Rules, was a humilation. Sheffield's one-man offside law, which spread play and enabled a passing game, bamboozled Manchester's dribblers, who were beaten 14-0. According to The Graphic it was a score that ‘has never been seen’ on a football field, ‘so easily did cotton go down before steel’. A month later Manchester captain, Stuart Smith, wrote to The Field calling for one set of football laws be produced. He didn't have long to wait long. On 17 April a unified association code for England was agreed after the Sheffield FA dropped its opposition to the three-man offside rule, and London accepted the throw-in.

The new FA rules certainly had the support of the medical profession. In October 1877 Britain's leading medical journal, The Lancet, published a stinging attack on rugby rules which, it claimed, was ‘rapidly degenerating’ into a ‘bear fight’, which gave ‘such a decided advantage to strength and weight rendered the game unfair as a trial of skill’. It called on club captains and secretaries to read a series of papers on football in the magazine Land and Water before deciding what rules to ultimately adopt, and noted

'We are glad, however, to learn that an increasing number of clubs have adopted the rules of the “Association Union”. Our strictures on the game as played under the Rugby rules are, we hope, now beginning to bear fruit, and the players themselves are commencing to discuss for themselves the propriety of making some modification in these rules, and rendering the game more one of football than of indiscriminate mauling, tearing and scrimmaging.'

That month Manchester Association tried out the unified rules at their new ground in Eccles, described as ‘not a very good one, being rather small’. The code didn't seem to suit opponents Broughton Wasps, with the Manchester Courier's match report noting the numerous free-kicks for handball conceded by the rugby club, who were ‘accustomed to pick up the ball at every opportunity’.

Broughton did not pursue any further interest in the association game. In fact, the only rugby club to show any enthusiasm was Birch, who played two games under association rules—against Glasgow’s Queen’s Park and Stoke— in April.

But Manchester Association were at least putting the game in the shop window. On 26 January 1878, they played Stoke at the ground of the Longsight Cricket Club on Stanley Grove, and returned there two weeks later to play Nottinghamshire.

We’ll never know if any of the young parishioners of West Gorton’s St Mark’s church watched the games. But two years later, on a field just a few hundred yards from the cricket ground, they had their baptism into the association game.

You can subscribe for free, below, and have the latest stories straight to your inbox.

My book on City’s origins, which covers the period 1880 to 1885, is available on Amazon here.

Part Six

Was reading only yesterday about queen's park still playing in Glasgow,but nowadays at a small purpose built stadium next door to the very large Hampden park.