The Birth of Football and the Origins of Manchester City

Part Eight: A Victorian Silicon Valley

This is where Manchester City Football Club was born.

The area is called West Gorton, and the above map shows what it looked like in the 1880s.

It was a very self-contained area—cut off to the north by the Manchester, Sheffield and Lincolnshire Railway, to the west by the London & North Western Railway depot and to the south by the giant Belle Vue Zoological Gardens—that hadn’t yet been incorporated into the city of Manchester.

Four decades earlier it was mainly pasture land, a mere handful of cottages and small farms that went by the name of Gorton Brook, part of the small township of Gorton.

But in 1842 the newly-constructed Sheffield, Ashton-under-Lyne and Manchester railway opened two stations: Gorton and Hyde Road. With two reservoirs, built in east Gorton in 1826, now supplying a million gallons a day, the area was primed for the arrival of heavy industry.

In 1846 work began on a depot for the new railway, dubbed the “Gorton Tank”. The man who masterminded its construction, Richard Peacock, then teamed up with German engineer Charles Beyer to build locomotives on land just to the south. In 1855 Beyer Peacock's Gorton Foundry opened, immediately producing a steam locomotive a day. Eight years later Peacock persuaded another iron magnate, Samuel Brooks, to move to Gorton Brook, where he built a giant works for his Union Iron company, the world's leading maker of machinery for cotton mills.

A low-tax enterprise zone quickly emerged in this self-governed township, prompting the type of growth that is nowadays only associated with China or the Gulf states. The iron barons oversaw the building of tightly-packed rows of terraced housing for their employees, along with sewers and street paving and lighting. They paid for the construction of churches and schools, while their works managers created a healthcare and welfare system.

The thriving district of West Gorton soon became a Victorian Silicon Valley—but without the sunshine. Or the valley. By 1880 it could could boast a literary society, a Mechanics Institute, an art night school, an array of social clubs and two thriving savings banks. It had also become a national transport hub following the opening in 1875 of Belle Vue station, which offered express trains to London, and other destinations, from its four spacious platforms.

West Gorton’s population had grown to more than 10,000 by this time. Around a quarter of them (mostly the younger inhabitants) had been born in the area, while roughly two-thirds were native Mancunians.

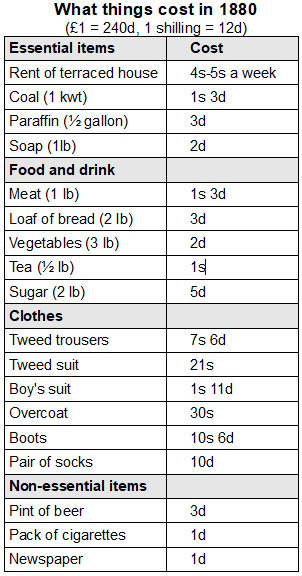

The Union Iron works, which at this time had 700-900 employees (workers were paid by the day, so the size of the workforce fluctuated with demand) dominated the area. For the men on the foundry floor the job was tough, dirty and often dangerous. But it was well paid. A typical wage was between 40 to 50 shillings a week—roughly double what most mill workers or manual labourers received. There was no income tax in Victorian England, and with a terraced house costing just 4 to 5 shillings a week to rent it left enough money for the luxury goods sold in the shops on the thriving thoroughfare of Hyde Road. Some iron workers could even afford domestic servants.

Families with working sons were particularly well-off. For instance, Union Iron works manager William Beastow, a church warden who also served on the Gorton Board, had iron workers living either side of his large home at the posh eastern end of Clowes Street. The household on one side, containing a 58-year-old iron works labourer Thomas Hobson and his three sons and son-in-law, enjoyed five wages. Running the household (including food and bills) cost around 40 shillings a week, leaving each man with a disposable income of 20 to 30 shillings a week.. That's a staggering amount of money, enough to afford a trip to the opera followed by a lobster dinner every night of the week, with enough left over for five pints of beer on the way home. Not for nothing that workers like these were later described as “the aristocracy of labour”.

There was one notable downside to life in 1880s West Gorton though. The acrid smoke spewing out from the many iron foundries, chemical works and passing steam locomotives, combined with the tons of horse manure that dropped onto the streets each day, produced a stench almost unimaginable today. And with an ever-present thick blanket of smog cutting out all sunshine, health was a constant worry. Gorton’s yearly death rate of around 25 per 1,000 was nearly three times today's figure. Bronchitis was the biggest killer followed by scarlet fever and tuberculosis. This was also an age before vaccinations and antibiotics, meaning that even a dose of the measles or a gashed knee could prove fatal.

Victorian Manchester was also a place where semi-darkness was the norm. For roughly two-thirds of the year West Gorton's residents would have walked to work before sunrise, along cobbled streets lit by dim gas lamps. Their homes were candle-lit and, given the high cost of candles, would be shadowy places. Pharmaceuticals were commonly used to lift the mood. Mothers routinely fed their young children opium-based cough mixtures (which in part explains the incredibly high child mortality rates), which were available over-the-counter at druggist stores alongside morphine, laudanum and “Indian hemp” cannabis cigarettes (dubbed the Victorian “wonder-drug”).

But it was music that most lifted the spirits. It would have been impossible to walk the streets of West Gorton without hearing its sound. There were street singers and bands, performing ballads, glees and minstrel musics, and barrel-organists—the original DJs—playing music-hall songs in the street on paper-roll organs. And there would be the songs and piano-playing coming from the area’s many public houses.

Gortonions were an incredibly musical people. The town even had its own philharmonic orchestra. That was partly the result of the 1870 Elementary Education Act, which designated payments of a shilling for each pupil with basic understanding of written music, plus 6d per head payment for singing three or four songs from memory. For a school such as St Mark’s, it meant that arount 15% of it’s annual government grant depended on their pupils being musical. It was common to own collections of sheet music, with colourfully-illustrated front covers, often kept in beautifully-bound albums, not too unlike the record collections of the later 20th century

The nearby city offered a staggering array of music each night. For 1s to 5s you could watch Mr Charles Halle's orchestra, or an opera, while a night of classic songs at a concert hall, or organ recital at the Town Hall cost 6d. For 3d you could experience the more bawdy popular songs of the music-hall, while in the “penny gaffs” (usually shops turned into temporary theatres) you could dance along to the songs. There were brass band competitions at Manchester’s pleasure gardens, military bands in the parks, concerts in workplaces, church halls and schools. There were glee clubs, fairground steam organs, spa orchestras and German street bands playing Italian arias and movements of symphonies.

Historian Asa Briggs called it the “Age of Improvement”, and for the educated and ambitious young men of West Gorton it was a world where anything was possible (not so much women, of course). Great improvements in child literacy meant that, as boys, they would have found inspiration in the pages of popular weekly magazines such as Boys of England. The magazine's tales of empire provided romantic role models, whose heroic exploits would have confirmed the belief once expressed by imperialist Cecil Rhodes that being born an Englishman was like winning a prize in a “lottery of life”.

Change was in the air in Manchester in 1880. The start of the year saw the opening of the city's first telephone exchange. It marked the beginnings of the electrical age, which the following year would see the first plans for electric street lighting in the city. Millions of working men would soon become enfranchised, the product of the Manchester-led Chartist movement of the 1840s, while in the leafty suburb of Moss Side in September, Christabel Pankhurst was born. Along with her mother Emmiline, she would later organise the first suffragette campaign from the Pankhurst's Manchester home.

Sporting change was also on the way. Little surprise then, that in November it was a group of ambitious young West Gorton men who would lead the way for Manchester’s entry into the world of assocation football.

You can subscribe for free, below, and have the latest stories sent straight to your inbox.

My book on City’s origins, which covers the period 1880 to 1885, is available on Amazon here.

Part Eight

Excellent informative writing