The Birth of Football and the Origins of Manchester City

Part Three: The Mighty Darwen

In September 1877 Athletic News noted that

‘Lancashire has unmistakably proved itself the headquarters of the “handling” style of play, but there are indications that the “dribbling” sport is making an unmistakable headway down in this district’.

Within two years the association game was king, with Lancashire’s many mill towns gripped by what one local journalist descibed as a “football mania”.

The transformation began in August 1878 when Thomas Hindle, secretary of Darwen FC, issued circulars to around forty local clubs suggesting the formation of an association for Lancashire.

At this time the clubs were playing a wide variety of codes, making cup competitions impossible. But at Darwen’s Co-operative Hall that month, 23 of them agreed to form the Lancashire Football Association, and play under London FA rules.

A month later eight clubs entered the newly-created Blackburn Challenge Cup, Lancashire’s first football knock-out competition. The competition, which was covered extensively in local newspapers, was an instant success.

Association cup competitions had also sprung up in Birmingham and Wales by this time. However, although more than 200 provincial association clubs now existed, entry to the only nationwide competition, the FA Cup, was prohibitively expensive. With most of the 43 entrants in the 1878-79 FA Cup based in the London area, a Lancashire side would need to find up to £30 to send players and officials there, way beyond the means of most working-class sides.

But the ambitious Darwen FC was developing a business model that would allow them to compete with the southern elite teams—one that became the springboard for the creation of a nationwide game. After entering that season’s FA Cup competition, the club spent £300 enclosing its Barley Bank ground, increasing capacity from 1,000 to 3,000.

Money was desperately scarce in Darwen that winter. With a savage nationwide depression called the Great Distress devastating the country, redundancies and pay cuts had resulted in emergency soup kitchens springing up in the area. Despite the hardship, the mill town's working people were still willing to pay 3d (the price of a pint of beer) to watch big matches.

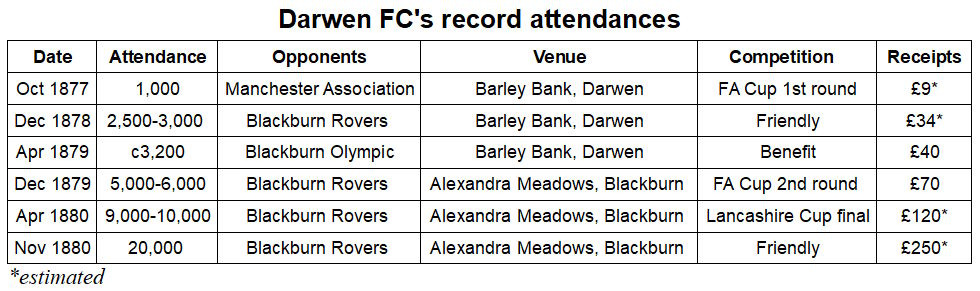

In December, 2,500 to 3,000 paying spectators watched Darwen beat Eagley 4-1 in the first round of the FA Cup, while 2,000 spectators watched them play Sheffield's Aftercliffe in a friendly at Barley Bank that month. The gate money for both games was around £60, enough to fund Darwen's trip to London on 30 January to play a side made up of former public school pupils, called Remnants, in the FA Cup second round.

It was the first time a provincial working-class club had played in the capital, prompting huge interest in Darwen. The town’s only newspaper, Darwen News, sent two reporters to cover the game and provided live goal updates via eletronic telegraph to fans who had assembled outside its Darwen office.

Darwen's 3-2 win set up a tie with England's most elite football club, the Old Etonions in the next round.

The class differences were immediately visible when the two side assembled at the Oval in London on 13 February. Due to generations of superior diet, the Etonions were on average two to three inches taller and stone or more heavier than the mill workers who made up the bulk of the Darwen side.

However, Darwen’s side included two Glaswegian players, Fergus Suter and Jimmy Love, who had brought with them a new way of playing. As the Etonions used their superior strength to bludgeon their way down the middle, Darwen, whose players were wearing lighter boots, countered with a passing game.

The match finished 5-5, and by the time Eton finally triumphed in the second replay on 15 March, “a kind of football mania” had taken hold of Darwen and surrounding areas.

As attendances grew, so did the financial rewards. In April, Darwen players shared the £40 gate money from a benefit match against Blackburn Olympic played before around 3,000 spectators. That was almost a month's wages for many mill workers and meant a player could, for the first time, make a living out of football.

The adulation reserved for the most skilful players also ushered in the birth of the football star. Later that month Suter and Love each earned around £10 for a benefit match arranged for them at Turton that attracted 1,500 to 2,000 spectators. In two games Suter had earned the equivalent of three months wages for a typical mill worker.

Before long Lancashire football would acquire another key characteristic of the modern game: hooliganism.

Only a handful of fields separted Darwen's 30,000 inhabitants from the mill town of Blackburn. Three times the size of Darwen, it was also richer—and not about to let its smaller neighbour steal the glory. At the start of the 1879-80 season its most ambitious club, Blackburn Rovers, secured the services of Darwen professional Hugh M'Intyre, marking the beginnings of the transfer market. In December the sides met in the second round of the FA Cup at Alexandra Meadows, Blackburn. A lively crowd of between 5,000 and 6,000, “large numbers” of whom had travelled from Darwen, watched Blackburn win 3-0.

According to one local paper

'it became only too evident that a number of Darwen roughs had assembled on the field… The game was temporarily stopped while the police cleared the crowd away. Unseemly shouting was prevalent throughout'.

The fixture generated around £70 gate money, enough to allow the best players to devote time to further improve their skills and fitness.

On New Year's Day 1880 Darwen reaped the benefits of professionalism when the Old Etonians played at Barley Bank. A new passing style was deployed that day. Darwen's 2-3-5 formation contained two full-backs, who played in a similar position to a modern-day centre-half, and three half-backs. With a forward playing on each wing the formation was not too dissimilar to a modern-day 4-3-3 with attacking full-backs. It was a passing game that marked the birth of the modern football, and would become football's standard formation until the 1930s. And it earned them a 3-1 victory.

Manchester became exposed to this new style of play in February, when the city’s only association club, Manchester Wanderers, visited Darwen in the third round of the newly-created Lancashire FA Challenge Cup. The new passing game bamboozled the Wanderers, who lost the game 11-0.

The Lancashire Cup soon became the most-watched tournament in the country. In April 1880 Darwen beat Rovers in the final replay in front of 9,000-10,000 spectators, a record crowd for an association match in England and 4,000 more than the FA Cup final. The gate money paid for a £150 solid silver cup, and covered the £50 cost of awarding a gold medal for each winning player and a silver one for losing finalists.

In July the 3ft 6in high trophy, claimed to be 'the finest of its kind in the kingdom', was officially presented to the victors. The Manchester Guardian, describing the trophy in intricate detail, noted that

'on the reverse side of the 'Renaissance Cellini-shaped' cup is the name of the first winner. “Darwen F.C., 1879-80,” with space for the names of future winners to be added.'

Football was now the stuff of dreams for young working men: giant silver trophies, gold medals, huge crowds of adoring fans, and the chance to earn a month’s wage in an afternoon. And as the Lancashire Cup trophy was exhibited in the principal towns of Lancashire that summer, the idea of emulating Darwen's glory began to capture their imaginaton.

Darwen's announcement that they had taken £270 in gate receipts that season also did not go unnoticed.

With football now able to generate sizeable profits, it was time for Manchester to take an interest.

You can subscribe for free, below, and have the latest stories sent straight to your inbox.

Part Three

I assume the darwen football club that exists today is the same one from way back ? Fascinating insight into British life 140 years ago .looking forward to the next one