The Birth of Football and the Origins of Manchester City

Part Seven: Mother of the Game

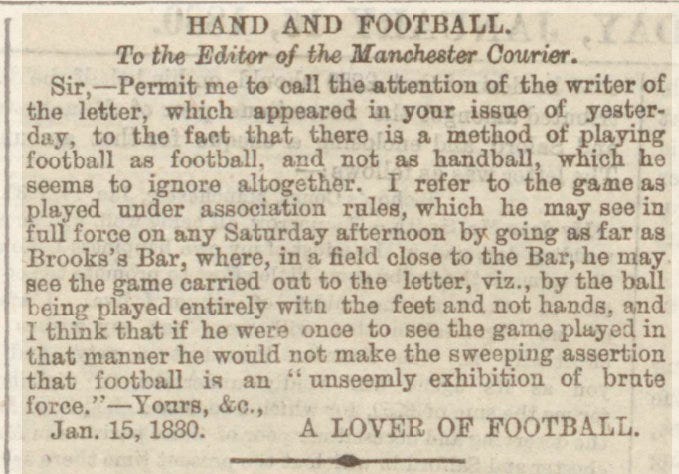

In January 1880 a letter was published in the Manchester Chronicle reminding readers that ‘there is a method of playing football as football, not as handball’.

Manchester by this time had established itself as a stronghold of rugby. There were now more than 100 clubs in the district playing the handling game. Only one club, Manchester Wanderers, played under association rules.

It had sprung from the Birch rugby club in September 1878 and included former players of Manchester Association, which had folded that summer. Like its predecessor, Manchester Wanderers’ membership was drawn from the upper middle classes. Club captain James Strang, for instance, earned £600 a year (worth around £370,000 today) from his family’s drysalters business on Portland Street.

Although Wanderers made occasional attempts to introduce local rugby clubs to the dribbling code, they seemed quite happy to remain as the city’s sole association club.

However, in November 1880 the number of Manchester association sides jumped from one to four.

On 13 November St Mark's played its first recorded game of association football against Baptist of Macclesfield at Belle Vue. The following Saturday two other Manchester sides, Newton Heath Lancashire & Yorkshie Railway (L&YR) and Manchester Arcadians, played their first recorded game of association football. That same day Clarence Association in Stalybridge (too far from the city to be called a Manchester side, but close enough to be of relevance) also played its first recorded association game.

All four sides were made up of working class or lower middle class players. Most of the St Mark’s players worked at the nearby Union Iron works, Newton Heath were a carriage works team, Arcadians were mostly cotton warehouse employees, while Clarence Association most probably originated from the Clarence cotton mill.

So what had prompted so many Manchester working people to suddenly take up the game?

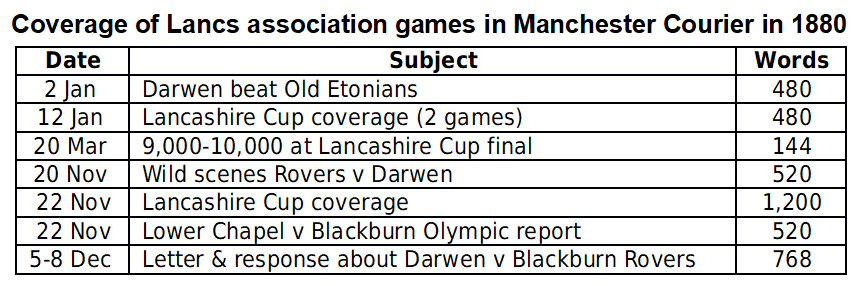

One possible explanation is the coverage of the Lancashire—and in particular Blackburn—association game in the Manchester press. Despite several attempts, Manchester’s rugby clubs had failed to create a knock-out tournament for their sport (something they would later regret after their code is overtaken in popularity by association). In the absence of a Rugby Cup, it was the FA Cup exploits of Darwen FC, and the excitement of the inaugural Lancashire Cup in the 1879-80 season, that were now grabbing the headlines in the sports pages of Manchester newspapers.

The physical ties between the three new Manchester clubs and Blackburn is also worth noting. The town would have been the biggest export market for Union Iron, the country’s largest manufacturer of machinery for cotton mills. With regular trips being made from West Gorton to Blackburn to secure sales and deliver orders, the passion that Blackburnians now had for the association game would not have gone unnoticed. The L&YR owned and operated both the railway lines that served Blackburn, while the cotton warehouse where many of the Arcadians players worked would have had daily shipments from Blackburn.

The creation of these new association clubs in the district also appears to follow a wider pattern.

At its second annual meeting 6 September, the Lancashire FA had announced that its intial membership of 28 clubs had now grown to 50. It also revealed that '19 new clubs had joined the Association, some of the districts being entirely new to the Association game, viz. Preston, Barrow, Great Harwood, Liverpool, Blackpool, Brinscal and Bacup'.

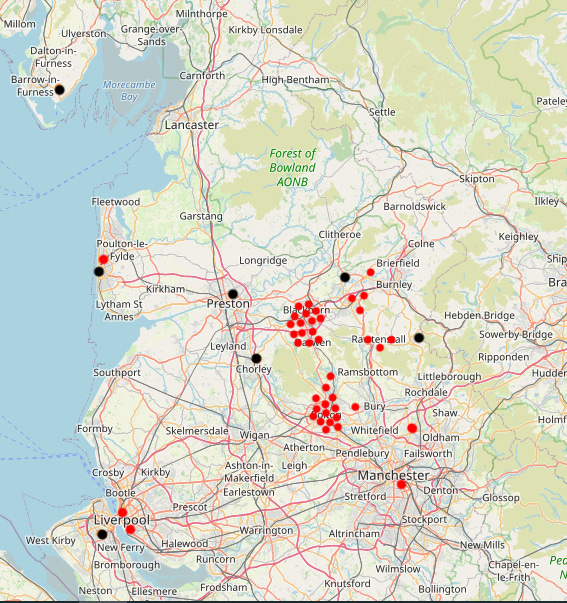

The red dots in the graphic below represent the location of the clubs that took part in the inaugural Lancashire Cup in the 1879-80 season, while the black dots denote the districts that the Lancashire FA claimed were new to the association game.

Although there is a large cluster of red dots in the Bolton area, most of the town’s clubs were eliminated early in the competition. Many suffered heavy defeats to Blackburn and Darwen clubs, suggesting that Bolton was relatively new to the association game.

So it appears that the spread of association football across Lancashire is not too dissimilar to a big bang, with the neighbouring towns of Blackburn and Darwen at its epicentre.

Certainly, the significance of Blackburn to the establishment of football in Manchester would become a feature of contemporary reports. Following the first Manchester Cup final in 1885, for instance, the victorious Hurst players retired to the Pitt & Nelson pub where the landlord, Joseph Fletcher, made a speech. According to The Ashton Reporter, Fletcher declared that he

“had been to Blackburn recently and he could assure them that the fame of the Hurst club was well known in that district and that he was certain that the next season they would be called upon to play with teams from that district, the Mother of the Game.”

You can subscribe for free, below, and have the latest stories sent straight to your inbox.

My book on City’s origins, which covers the period 1880 to 1885, is available on Amazon here.

Part Seven

Excellent piece as always