The Birth of Football and the Origins of Manchester City

Part Nine: The Hand of God

The story that St Mark's church created a football team in order to lure the young men of the district away from gang-fighting known as “scuttling” is now a well established one. In 2015 City's head of infrastructure Pete Bradshaw described the club's origins as a “crime diversion programme”, a claim repeated by City's CEO Ferran Soriano in a podcast interview in 2022.

Unfortunately, the story isn't true.

It first appeared in Peter Lupson's 2006 book, Thank God For Football, which examined the church's role in the creation of eleven Football League clubs. But his chapter on City's origins didn't contain any evidence linking St Mark's to scuttling. Instead, the claim was based on the twin assumptions that social conditions in the poorer parts of Manchester were also present in West Gorton, and that this must have been the reason for the team's creation.

But as Part 8 shows, West Gorton in 1880 was a thriving iron district. Local newspapers contain no reports of youth crime in the area at this time, or much crime at all. In fact, the area's police superintendent declared at the end of that decade that “he did not believe there was a township anywhere of the same population so free from real crime as Gorton.”

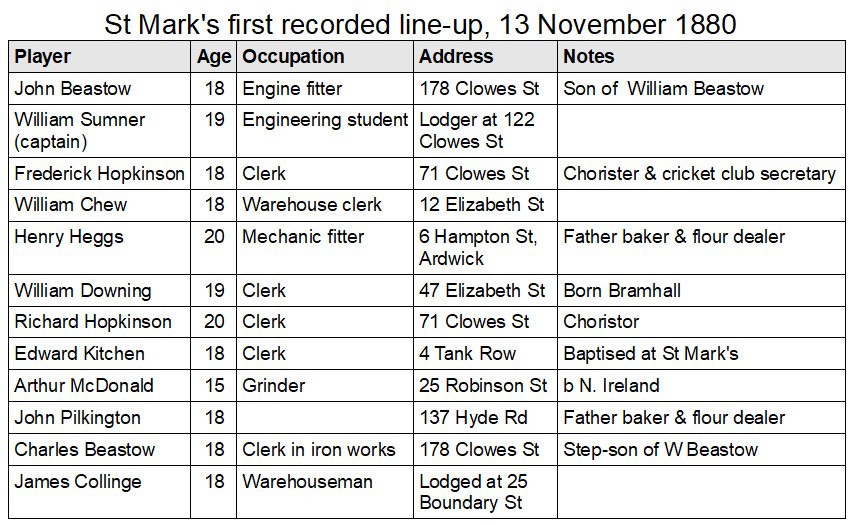

In fact, the St Mark's players were mostly the posh kids of the area. Their first captain, William Summer, was a university student (an exceptionally rare thing in those days) while the side also included the son and step-son of the Union Irons works manager, William Beastow, and the sons of the church organist. Less Peaky Blinders, more Choir Boys FC.

So why did St Mark's create a football team?

On 6 November 1880 Manchester's Bishop Fraser delivered a keynote speech at the city’s cathedral. It was only his third “visitation” in a decade as bishop, and he used it to spell out the most pressing concern facing the Church at that time: the problem of young men.

Fraser revealed that over the previous 11 years only 14,050 young men had been confirmed into the Manchester Church compared to 73,754 young women. He told the assembled clergymen that the increasing disparity indicated a “prevalence of the notion that the profession of religion is a thing for women rather than men”. Young men who wanted to stay in the Church were “subjected to annoyances and ridicule”, he said. The notion that religion was unmanly was one that the Church “must fight against with all the resources that are at our command,” Fraser declared. It was a task that required “the ripest wisdom and maturest pastoral experience”, and should "not to be delegated to the young curate or scripture-reader”.

St Mark’s rector, Arthur Connell, was one of the clergymen in attendance that day. That afternoon a new rugby side, called St Mark's Rovers, played its first recorded match against Lawn (possibly Audenshaw's Beech Lawn Cricket Club) at West Gorton. The following Saturday another St Mark’s side played its first recorded game of association football, against Baptist of Macclesfield.

While it is impossible to be certain about the exact motivations of people now long dead, Connell was on the evangelical wing of the church and a believer in what was then called “muscular Christianity”. This was the belief that a healthy body led to a healthy, and holy, mind, and Connell's creation of a football team does appear to appear to be an example of this belief at work (it’s also worth noting that Connell, who had been asking for a curate for his parish for some time, was keen to win favour with the bishop).

It's likely that the St Mark's players were member of the church's Sunday school. A month earlier, at the Church of England's Sunday school centenary celebration at Manchester's Association Hall, a succession of speakers had revealed that the Church had been losing ground to the non-conformists. One warned that non-conformity “was assuming gigantic proportions and gaining fresh ground”, in large part because of the “wonderful machinery” of their Sunday schools. He noted that these schools were having “unequalled success in retaining elder scholars”. Calling on the assembled clergymen to recognise the “existing abuses and defects” of their schools, he also called on them to utilise “supplementary aids out of school”.

The formation of football clubs elsewhere also suggests a Sunday school connection. Seven of the nine present-day major League clubs with church origins are now known to have originated from Sunday schools (Bolton, Fulham, QPR, Southampton and Tottenham had Church of England origins, Aston Villa was Wesleyan and Everton was Methodist). More specifically, they originated from their schools' Young Men's Bible Class, which typically consisted of men in their late teens and early 20s.

The average age of St Mark's football team that first game was 19, representing precisely the age group the Anglican church had admitted it was struggling to retain. According to Paul Toovey's Birth of the Blues, nine of the 12 players that played in St Mark's first football match had in 1879 appeared for a St Mark's side called the Juniors—a popular name for Sunday school clubs. It also seems significant that none of them played for the Juniors side in 1880, suggesting they had progressed from a junior class to the young men's.

Of course, it should also be remembered that the creation of the football team was essentially a bribe to keep young men involved in the church. There were plenty of other sports these men could have chosen, while activities such as picnics were commonly organised by Sundays schools at this time. Instead, they chose to play a game that barely existed in Manchester at that time.

So why was the St Mark’s side created? I suppose the simple answer is that these young men just wanted to play football.

Part Ten will be published on Saturday 31 August.

You can subscribe for free, below, and have it sent straight to your inbox.

My book on City’s origins, A Man’s Game, is available on Amazon here.

Very good informative piece .