The Birth of Football and the Origins of Manchester City

Fifteen: To Glory We Steer

Following Gorton's 5-0 win at home to Manchester Clifford on 10 January 1885, the local newspaper declared:

‘The Gorton Association Football Club, newly formed this season, have taken all before them. They beat a strong team of the Manchester Clifford on Saturday by five goals to nil. They have really only lost one match this season, and that was with only half their team at Tottingham Park. This is good form, and the success of the club has caused whispers that it would not be very surprising to hear of them bringing the Manchester and District Challenge Cup to Gorton.’

Local newspapers did not employ sports reporters at this time, instead relying on information provided to them by clubs. So this particular report would have been written by someone on Gorton’s club committee—and is one of the earliest examples of media hype involving a Manchester football club.

Indeed, a 3-1 defeat at home to Newton Heath on 17 January, in which Gorton were outplayed during much of the game, showed that there was still a long way to go before they could compete with Manchester’s more established sides.

Gorton were knocked out in the first round of the Manchester Cup, losing 1-0 to Dalton Hall on 31 January (the game was played at Maine Road, though not near the site of City’s later ground). But it appears that around this time they suffered a more important blow.

Gorton’s home games were being played at a cricket ground on the western side of Pink Bank Lane. But their last recorded fixture there that season was a 3-0 win against Manchester Clifford on 24 January, with a match report noting that the ground was ‘very much against good play’. According to the 1906 Book of Football, the club was evicted from a ‘Kirkmanshulme Cricket Ground’ after the cricketers became ‘very irate’ at the state of the playing surface. Although this account dates this eviction to an earlier season, the financial accounts for Gorton’s 1885-86 season included £2 compensation for “loss of ground”, indicating that they had been evicted from Pink Bank Lane.

Gorton are only recorded as playing two more games that season. After a 1-1 draw away to Gorton Villa on 14 February, they travelled to Newton Heath a week later. But a 6-0 defeat to that season’s Manchester Cup finalists illustrated a growing gap between Gorton and their local rivals. According to a match report, Newton Heath’s ‘tactics were more combined and their passing at times was very fine.’

Despite the setbacks, Gorton AFC’s first annual dinner on 20 April, was an upbeat affair. After reading the annual report, which revealed the club had around 25 active members and the promise of ‘a good increase’ the following season, treasurer Frederick Hopkinson performed a rendition of The Old Brigade, a popular march written in 1881 by Edward Slater (who also composed Danny Boy). W Chew (probably William due to his age and his position as Gorton's umpire) then led the singing of the naval march Hearts of Oak. That song was the Victorian equivalent of a terrace anthem, and its lyrics probably give a good insight into the mindset of the club's members that evening:

“Come, cheer up, my lads, 'tis to glory we steer,

To add something more to this wonderful year;

To honour we call you, as freemen not slaves,

For who are so free as the sons of the waves?

Heart of oak are our ships, jolly tars are our men,

We always are ready; steady, boys, steady!

We'll fight and we'll conquer again and again”.

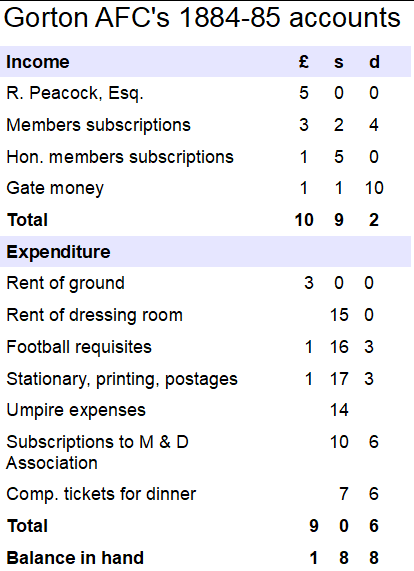

At this time Gorton AFC were near the bottom of the country's football pyramid. The club's accounts reveal that only £1 1s 10d was taken in gate receipts that season, the equivalent of just 23 spectators per match paying 3d each (a typical admission charge at that time). To put its finances into perspective, that season's £10 9s income was almost 200 times less than that of Bolton Wanderers, who recorded a turnover of £1,949 in 1884-85.

However, there were good reasons for optimism.

Football was now booming, with crowds of 15,000-plus being recorded at matches in Blackburn, Bolton, Nottingham and Derby. ‘On every vacant piece of land can be seen the schoolboy and operative giving an exposition of its rules,’ the Preston Guardian wrote in August 1884. According to a January 1885 edition of The Athlete,

‘Never in the memory of man... has any game attained such a wonderful popularity, and the public interest, instead of waning, grows stronger year by year’.

Although still a footballing backwater, interest in the game was now growing in Manchester. The final of the inaugural Manchester Cup in April 1885, which saw Hurst defeat Newton Heath 3-0, had attracted a 3,500 crowd, while Gorton’s game at Gorton Villa was played in front of a ‘large number of spectators’.

It appears that Gorton AFC had also been attracting reasonable crowds that season (a match report noted a “fair number of spectators” for the home game on 22 November), suggesting that most spectators had been watching for free due to the ground not being properly enclosed.

But that summer the club finally secured a fully enclosed ground, on land adjoining the Bull’s Head pub on Reddish Lane, near Gorton’s eastern border with Reddish. The location wasn’t ideal. The ground was more than two miles from where most of the players lived, while the surrounding area was much more sparsely-populated than West Gorton.

However, the move marked the start of the club’s relationship with the brewing industry—one that was about to transform its fortunes.

My book on City’s origins, A Man’s Game, is available on Amazon here.

What was the first song at City? Why did Steve Coppell resign? Did City have a “Fifth Column”? Did the IRA try to burn down Hyde Road? Who started the “banana craze”? And what was Maine Road's Scoreboard End called before there was a scoreboard?

All these questions—and more—are answered in my latest book, available on Amazon here.

You can subscribe for free, below, and have the latest stories sent straight to your inbox.

Excellent read