The Birth of Football and the Origins of Manchester City

Part Eleven: The Ungodly Game

The picture of City's formative years will always be an incomplete one: a mosaic with most of its pieces missing.

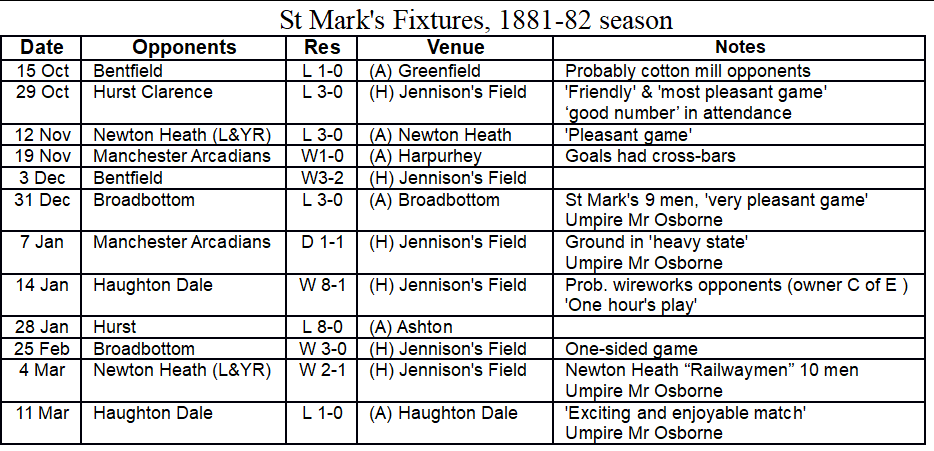

But what is clear is that St Mark's made notable progress in the 1881-82 season. Bolstered by new players from manual occupations—a machine works apprentice, boiler maker, wagon maker, fitter and clog maker—St Mark's won five of their 12 recorded games. The highlight of the seaon was a 2-1 victory over Newton Heath on 4 March, the winning goal being celebrated 'amidst loud cheers' from the large Longsight crowd.

Whether the young men of St Mark's were playing football on the other Saturdays—and for whom—will probably never be known. Nor will we know how much footballing activity took place involving the district's many iron works. That type of football was not deemed worthy of newspaper coverage.

But the Gorton Reporter does contain reports of two matches that season involving another West Gorton club, Belle Vue Rangers. On 14 January 1882 they are recorded playing Hurst Park Road in Ashton, and two weeks later played Hurst Park Road's reserve team on public land known as Clemington Park in West Gorton.

It's possible that these matches were deemed newsworthy because they involved a side from outside the district. Or it may be that, in an era before match reporters, someone at the club had taken the trouble to send the details to the newspaper. If so, that person was most likely Belle Vue's 17–year-old captain Walter Chew, the younger brother of St Mark’s regular William—and a key figure in City's early development.

The two sides played just a stone's throw from each other that season (Clemington Park was across from Jennison’s Field on the northern side of Hyde Road). But they represented two very different footballing ideals.

Unlike St Mark's, Belle Vue was a members club. Its inspiration would have been drawn from the growing exploits of Blackburn football—and its riches. On 18 March 1882 a game between Darwen and Blackburn Rovers attracted close to 20,000 paying spectators. The following month Rovers became the first working-class side to reach FA Cup final, losing to the Old Etonians.

But St Mark’s church had little interest in large crowds or trophies. And the idea of paying young men to play sport would have been abhorrent to the likes of Rev. Connell.

Around this time religious bodies lost control of many of the sports teams they had founded, including the Christ Church Sunday school side in Bolton, which cut its ties with the Anglican church in 1877 and re-formed as Bolton Wanderers. The young footballers of St Mary's Young Men's Association in Southampton would also cut their ties with the Anglican church after being told that would have to teach in the Sunday school in order to remain in the side, renaming themselves Southampton FC in 1887.

And it appears something similar happened at St Mark’s in the 1882-83 season. Again, the picture is unclear. There was certainly continuity in the line-ups throughout the 1882-83 season, though match reports all referred to the side as 'West Gorton', while newspapers commonly listed them as West Gorton (St Mark’s) on the results page. But as the side now played at a new home ground, most probably the land next to the Union Iron works known as Farmer’s Field, it’s likely that a split from the church had taken place.

While that offered the prospect of gate money and glory, moving away from the church’s authority also carried its risks. The players were now separated from the Church's concept of “Muscular” Christianity, that sport was a means to create good moral character in young men. Central to this idea was the belief that “fair play” was more important than winning, with games overseen by an older and respected umpire who could curtail the excesses that were allowable under the rules.

The level of violence in both association and rugby codes had reached dangerous levels had reached dangerous levels during the 1882-83 season. In October the Courier's football correspondent even claimed that the ‘dribbling game’ may have been the more violent. Listing the injuries that had occurred in association games in the Manchester area during one Saturday, he noted that,

‘A collar bone was broken at one place, a jaw bone and nose were, to quote the wording of the announcement, "smashed" at another, whilst a gashed face, requiring the immediate attention of a surgeon, was all that resulted in the third.’

Finding eleven players for matches became increasingly hard for both West Gorton and Belle Vue. West Gorton were a man short for a game on 28 October, and on 4 November could only muster eight players for the game at Hurst Clarence.

Belle Vue Rangers' 5-4 defeat away to Endon Reserves on 4 November 1882 was described as a 'very unpleasant game' in which Belle Vue were forced to play against the wind for 75 minutes after Endon refused to change ends at half time. According to a match report, ‘both of the umpires' watches were found to be stopped when time should have been called’. Belle Vue's game away to Macclesfield Wanderers was even more bad-tempered, as the home side ‘played a rough game even charging their opponents when the ball was six yards over the goal line’.

In December 1882 the problem of violent play was debated at a meeting of the Football Association's National Conference held in Manchester. The Conference proposed changes to the sport's rules, which were published on 8 January 1883. Rule 10, which stated that “Neither tripping nor hacking shall be allowed, and no player shall use his hands to hold or push his adversary” now read (changes in italics):

Neither tripping nor hacking, nor jumping at a player, shall be allowed, and no player shall use his hands to hold or push his adversary, or charge him from behind.

Although going some way to curtail the violence, “charging” a player head-first was still permitted, as was kneeing an opponent and “jumping at a player” who was shielding the ball with his back to goal. And with referees' cautions not yet a part of the game and sendings-off only permitted for the possession of dangerous footwear, even the most violent breach of the rules would have resulted in little more than a free-kick to the opposition team. For the time being, Manchester's young footballers were being offered scant protection from brutal play.

On the day the revised rules were published, the Manchester Courier's “Football Notes” read more like the in-patient records of a hospital casualty ward. In a rugby match at Whalley Range, one player ‘deliberately seized a diminutive player of the opposite team, who had just wriggled his way through a scrummage, and after lifting him into the air, smashed him, with all his full force, full length to the ground’. In another match in Manchester the previous Monday the most gifted player on one team ‘was generally knocked into a jelly’ and finished the match unconscious with a sprained ankle, twisted knee, wrenched shoulder, severely bruised arm and a bent nose, while a Darwen player was ‘seriously injured’ after he was knocked unconscious by a kick to the ribs (labelled “charging”), the third serious injury to a Darwen player that season.

In a time before universal healthcare and benefits, when a serious injury could result in severe financial hardship, the playing of football had become too risky for many young men.

Soon it would take the life of one young Gorton footballer.

My book on City’s origins, A Man’s Game, is available on Amazon here.

What was the first song at City? Why did Steve Coppell resign? Did City have a “Fifth Column”? Did the IRA try to burn down Hyde Road? Who started the “banana craze”? And what was Maine Road's Scoreboard End called before there was a scoreboard?

All these questions—and more—are answered in my latest book, available on Amazon here.

You can subscribe for free, below, and have the latest stories sent straight to your inbox.