The Birth of Football and the Origins of Manchester City

Nineteen: Football's First Spending Spree

On 2 May 1890, at a meeting Douglas Hotel in Manchester, Sunderland became the first new club to be admitted to the Football League since its formation.

Membership of the two-year-old League still reflected the game’s early development, with only two of its twelve clubs, Everton and Aston Villa, based in a city (Sunderland wasn’t granted city status until 1992). However, Everton’s average attendance of 10,100 in the 1889-90 season—nearly double the League average—pointed to a challenge to the established order.

The growing popularity of the game in cities such as Manchester and Newcastle was prompting fears that big-city clubs would one day dominate the League. Manchester’s bid for League representation had been firmly rebuffed a year earlier, when Newton Heath’s application received only one vote (out of 48) at the League’s AGM. Their application was also rejected at the Douglas Hotel meeting.

However, now it was Ardwick’s turn to attempt to break into the top tier. And this time they’d do it the Mancunian way.

In May 1890 club president Stephen Chesters Thompson provided the funds for football’s first ever spending spree. Committee member John Allison and club secretary Lawrence Furniss (both future City chairmen) were tasked with signing new players. According to Empire News,

‘they hunted Scotland and England for the best men that could be got’

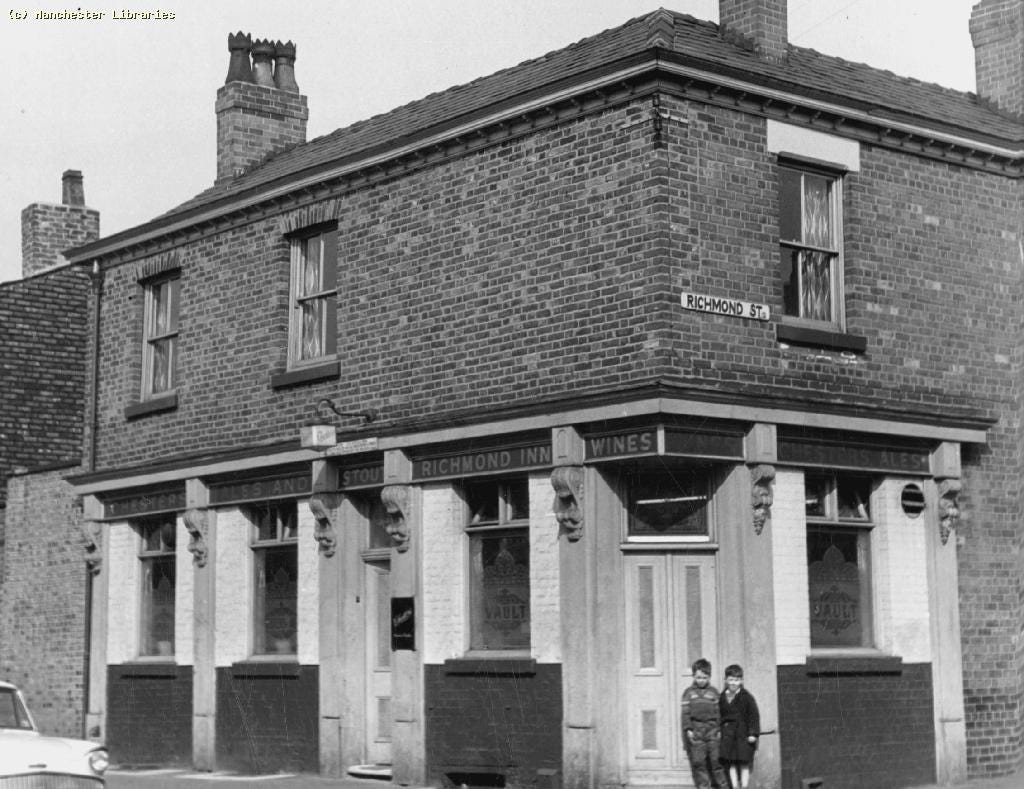

Thirteen professionals were signed that summer, six of whom were enticed from Football League members Bolton Wanderers. The most astonishing signing was Bolton’s international forward David Weir, who joined for £5 a week (the maximum weekly wage was set at £4 in 1901). He was also given the licence of Chesters' Richmond Inn pub on Stockport Road, making him the highest paid player in the land.

The final bill for this all-star XI came to £600-£700 which, added to the £600 spent on ground improvements, meant that the club had spent more than six times the gate money for the previous season. Almost twice as much, in fact, as the level of investment Sheikh Mansour put into the club in his first season as owner.

Newspapers reacted in horror at what Empire News described as ‘Ardwick’s bold bid for the supremacy of Manchester’. On 26 May Athletic News wrote,

‘They get very good “gates”, but if they pay their players at anything like the rate at which they have engaged Weir they will finds themselves in the Bankruptcy Court.’

And it wasn’t long before the “money can’t buy success” brigade were in full voice. In September one newspaper poured scorn on the club for

'thinking that it was possible to get a first-rate team together by the mere expenditure of money. It needed something more – labour, practice, patience, training, and coaching being as necessary as hard cash before they could compete with Preston North End and Bolton Wanderers.'

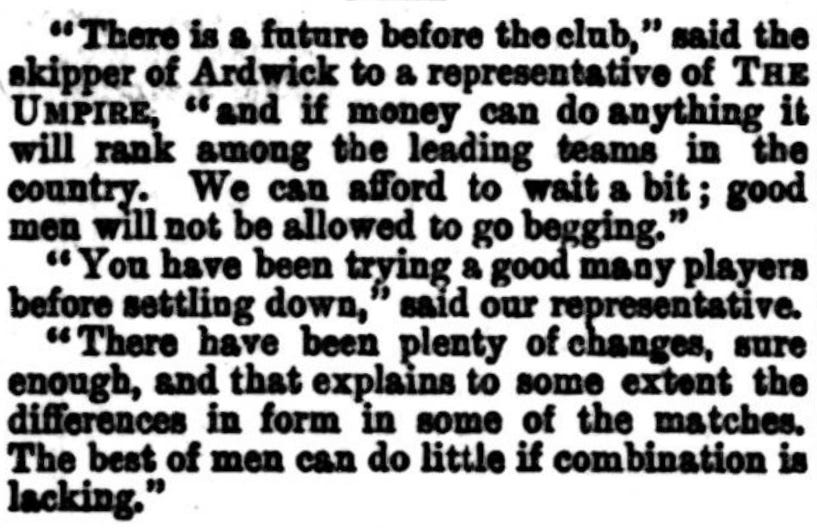

New club captain Weir hit back at the critics the following month, proclaiming:

“There is a future before the club, and if money can do anything it will rank among the leading teams in the country.”

But the Football League had other ideas.

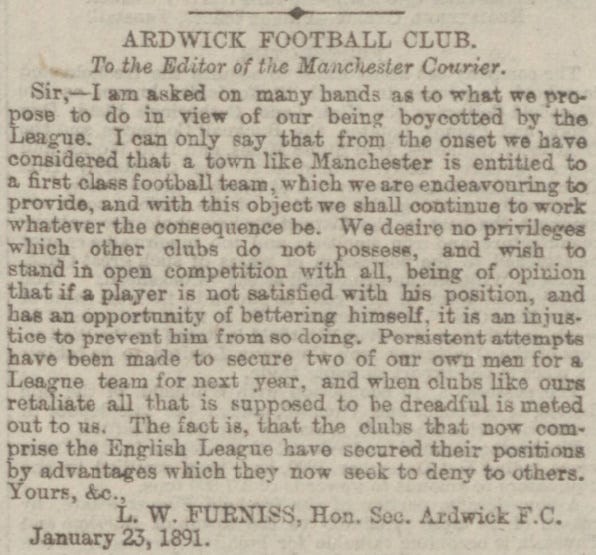

In January 1891 it banned Ardwick indefinitely from playing matches with League clubs—the first boycott of its kind. Furniss immediately hit back against the ban. In a letter to the Manchester Courier he wrote:

‘From the outset we have considered that a town like Manchester is entitled to a first class football team, which we are endeavouring to provide, and with this object we shall continue to work whatever the consequence be… The fact is, that the clubs that now comprise the English League have secured their positions by advantages which they now seek to deny others.'

However, after rumblings of a breakaway “Northern League” that month, which would have included Ardwick, Newton Heath and Bury, the Football League relented. In February it lifted the ban—and Ardwick’s meteoric rise continued.

On 7 February 10,000 fans watched Ardwick beat Bury in the Lancashire Junior Cup at Hyde Road. Three weeks later a sell-out crowd of 11,000 turned up for the visit of Newton Heath. In March they reached their first Cup final, losing 3-1 to Blackpool in the Lancashire Junior Cup. Following the game, Athletic News wrote:

‘Ardwick and the Junior Cup have parted company. Blackpool proved much too strong for them at Preston on Saturday, and defeated them by three goals to one. Hence all the good things promised Ardwick by Mr. Chesters-Thompson if they brought the pot back to Manchester will have to find a resting place elsewhere, including the £100 dinner.’

That is a staggering amount for a dinner, the equivalent of around £30,000 in today’s money. And the money kept flowing.

In April Hyde Road got its first stand behind a goal. It was '75 yards long and 14 tiers deep' and became known as the Galloways End. And, in true Victorian style, it took just seven days to build.

That month Ardwick won its first silverware, after David Weir scored the only goal against Newton Heath in the Manchester & District Cup final at Whalley Range. According to Athletic News,

'Ardwick played infinitely better football, and the issue was never in doubt from the very beginning.'

In May, the newly-crowned kings of Manchester football applied for membership of the Football League. On 10 May the Sunday Chronicle reported that,

‘It was a near thing, so I am told, for Ardwick being affiliated by the League, as Derby County only beat them by one vote, the numbers being 6 to 5. If Alderman Chesters-Thompson’s hobby had been successful in their application, the Association game of football would have got a lift in the district which would have done positive wonders for the pastime.’

Undeterred, Ardwick were accepted into the Football Alliance, a rival to the Football League that had been formed a year earlier. Now one of the best-supported clubs in the country, it was only a matter of time before Ardwick broke into football’s top tier.

But Chesters Thompson’s “hobby” served a bigger purpose. With a General Election looming it was now time to tether Manchester’s premier club to the cause of the ruling Conservative Party.

City were about to invent “sportswashing”.

My book on City’s origins, A Man’s Game, is available on Amazon here.

What was the first song at City? Why did Steve Coppell resign? Did City have a “Fifth Column”? Did the IRA try to burn down Hyde Road? Who started the “banana craze”? And what was Maine Road's Scoreboard End called before there was a scoreboard?

All these questions—and more—are answered in my latest book, available on Amazon here.

You can subscribe for free, below, and have the latest stories sent straight to your inbox.

Excellent piece as always.