City’s Annual General Meeting in June 1904 was upbeat affair. The FA Cup holders announced a record turnover of £13,384 for the season—up more than a third on the previous highest—and record profits of £2,250. Although eyebrows were raised at the £1,549 cost of signings—another record—as director Joshua Parlby explained,

‘His experience of sport was that they could only do great things with great cost. They could not have the money and the bun as well.’

Travelling, hotel and training expenses had also risen sharply, though manager Tom Maley informed shareholders that City ’‘had done more special training than any other club” that season, usually at seaside resorts. Better preparation for away matches had also increased costs. Maley explained:

‘A lot of money had been paid this year in connection with the matches in the far north by taking the players there a day or two previous to the matches. The results had justified the policy.’

As a result, Maley assured the ‘very large’ number of attendees that they had “every reason to look forward to a successful season”.

But one important issue remained unresolved at the AGM.

The decision of press baron Edward Hulton to stand down as chairman had created a power vaccuum in the boardroom. The brewing interests, led by former chairman John Chapman, now saw an opportunity to win back control of the club. Their opponents included John Allison, Hulton’s closest ally, who was re-elected to the board at the AGM following a year’s absence.

On 5 July a group of directors held a meeting at Chapman’s Shakespeare Hotel in Ardwick. A decade earlier a meeting of former Ardwick FC committeemen had taken place there, where it was decided to form a new company, The Manchester City Football Company Limited, to take over the running of the club (see this story).

The transition from Ardwick to City had placed control of the club in the hands of the district’s brewing interests. Hulton’s plans for a new stadium at Belle Vue had threatened a loss of income in their Ardwick pubs. But with the press baron now out of the way, the assembled directors voted to kill the move.

Instead, Hyde Road’s 30,000 capacity would be ‘increased to at least 40,000’ by extending the grandstand and enlarging the “Stoneyard” and Galloway stands. Owing to the absense of ‘one or two members of the directorate’ a vote to appoint a new chairman did not take place. But the brewing interests on the City board had sent a clear message that they wanted their club back.

The timing couldn’t have been worse.

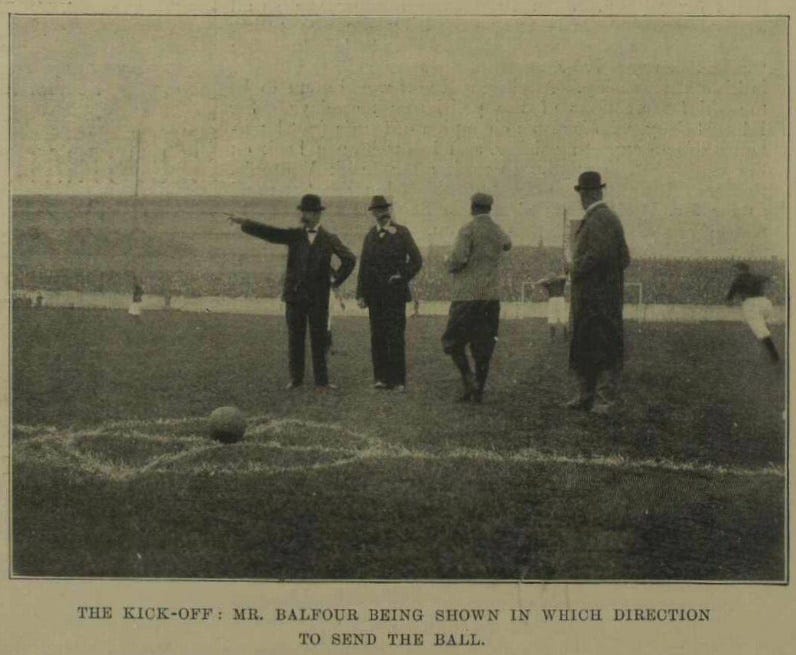

That month a new Licensing Bill, which gave local magistrates sweeping powers to refuse alcohol licences, was being debated in parliament. Although Prime Minister Arthur Balfour had enjoyed close ties with the brewing industry (as MP for Manchester East he had been backed by City’s biggest shareholder, Chesters Brewery) the temperance movement was now on the rise.

Following the passing of the bill, football became the movement’s main focus.

On 10 September Manchester magistrates banned the sale of alcohol at both City’s Hyde Road and United’s Bank Street grounds (though not at the Old Trafford cricket ground, where bars remained open seven hours a day). But that was only the beginning of City’s troubles.

FA president Arthur Kinnaird, a leading temperance campaigner, now had the club firmly in his sights. Although FA secretary Frederick Wall (whose mother had died from alcoholism) had been unable to find evidence of wrongdoing in City’s books, an investigation into the signing of Irvine Thornley and Frank Norgrove from Glossop in April had proved more promising.

It was certainly an unusal transfer deal. City had withdrawn £175-worth of gold from the bank that month via a cheque made out to the Glossop secretary, though neither party could show where the gold ended up.

Although an FA Commission failed to find evidence that Thornley had received more then the permitted £10 signing-on fee, it concluded that

‘they have evidence that after the transfer both he (Thornley) and his father endeavoured to obtain further payment from the Glossop club, and also that the father stated that he had received a sum of money from the Manchester City club.’

On 7 October the FA Commission handed City the harshest sanctions even seen in football.

Directors John Chapman, Lawrence Furniss, Joshua Parlby and Charles Waterhouse were suspended ‘from taking any part in football or management’ from 4 November 1904 to 1 May 1907. Finance director George Madders was suspended for life. Thornley was banned for the remainder of the season, while his father received a life ban from associating with any football club. City were also suspended from playing any matches between 11 October and 8 November, and fined £250.

The sanctions came as a complete shock to the club’s directors. None of them had been informed of the charges against them during the Commission’s investigation. Nor were they notified of its findings, which they only found out about from journalists.

In an interview at his Wellington Hotel pub that evening, Parlby showed a telegram from Maley to a Manchester Courier reporter. It read:

‘Astounded: feel worse than can express. Coming down.’

But most shockingly of all, it appears that the FA had resorted to illegal methods in its pursuit of the club. On 10 October the five suspended directors signed a letter that referred to a ‘drawer-breaking episode’ during the FA’s investigation:

‘Previously we had been told, indeed it was public property, that, acting on behalf of the FA, certains parties had called at the address of the Glossop secretary in his absence, and, obtaining access to his books, and made extracts therefrom.’

The club had received an official communication from the FA by the time of a meeting of shareholders and directors on 20 October, which was read out to cries of “Shame”. Although legal action had been discussed, a statement by the directors revealed that FA rules did not permit them to appeal a decision, or take the matter to any other body.

Chapman did admit that they had “done little irregularities as far as the Football Association laws go”, but argued that it was now “impossible” to do otherwise if they wanted to be competitive. Maley added:

‘If all the innocent people amongst those who had criticised the Manchester City club were to leave their visiting-cards at Hyde Road, a common match-box would contain the lot.—(“Hear, hear,” and laughter.)’

City had got off to a poor start that season, with just one win and two draws from their opening five League games. In September winger Billy Meredith had lost both his parents in the space of a few days. The bereavement appears to have affected his form, while striker Thornley had struggled to adapt to ‘the methods of his colleagues’.

But following the 20 October meeting

‘Maley advised that the misfortunes of the past should be forgotten as quickly as possible, and the full energies of all associated with the club directed towards the achievement of great triumphs in the near furture.’

It was time for City to do their talking on the pitch.

Part Seven will be published on Saturday 6th April.

You can subscribe for free, below, and have it sent straight to your inbox.

Chester’s brewery went years ago , it was taken over by whitbread and the Chester’s name disappeared from all pubs soon after . Look forward to the next update

Wow …another great piece . How interesting that ex PM Balfour whose name has been in the media of late due to the troubles in the Middle East and his significant historical part in it , should have played a part in city’s history! Chester’s brewery was in green gate Salford and the aroma could be smelt around deansgate in the mid 70s when I started work . Keep up the excellent work