1894 Explained

Why Ardwick became Manchester City

To understand the events of 1894 we must first re-trace our steps to four years earlier, when City was a small semi-professional club named Ardwick.

Early in 1890 club president Stephen Chesters Thompson spent £600 (around £470,000 in today’s money) turning the primitive Hyde Road enclosure into a modern 11,000-capacity stadium, complete with its first turfed pitch. In May he spent a further £600 to £700 signing 13 top professionals from League clubs.

The spending was around six times the gate money for the previous season. Not too different, in fact, to the level of investment Sheikh Mansour put into the club in his first season as owner.

The side was assembled by Chesters Thompson’s next door neighbour, John Allison, whose hydropathic baths clinic on Hyde Road had provided him with invaluable knowledge of muscular and limb injuries. It was managed by Lawrence Furniss, an early captain of the club when it was called Gorton.

After winning the Manchester Cup in 1891, Ardwick joined a rival to the Football League called The Alliance. They retained the Cup in 1892 and shortly afterwards joined the Football League, after it incorporated The Alliance as its Second Division.

The club’s funding had come from Chesters Brewery, where Chesters Thompson was chairman (in 1890 Bolton’s England international David Weir was given a Chesters pub, the Richmond Inn, when he signed for the club).

But in August 1893 a financial crisis at the brewery resulted in Chesters Thompson being forced to resign. After an internal audit, the new chairman discovered that the company had spent £2,600 on the club (around £2.2million in today’s money). After demanding immediate repayment, in October the brewery’s solicitor was instructed to launch legal proceedings.

The following month a new club committee was elected at a meeting at the Hyde Road Hotel. They were: Samuel Holden, Alexander Strachan, John Prowse, Robert Hayes, W Ashworth and a man just recorded as ‘Coates’.

They faced a daunting task. On 4 December the Athletic News reported,

‘The Ardwick Club are going from bad to worse, and the old and present members of the committee have to face an application from Chesters Brewery Co. for the payment of the sum of £1,600. We are not well versed in the law, but should imagine that Chesters Brewery Co. have as much chance of recovering the amount as say Darwen have of winning this year’s League Championship. Added to this is a debt of £500, so that it may be imagined that the prospects of the Ardwick Club are anything but bright.’

Because Ardwick was a members club, every committee member from 1890 onward was now liable for their share of the debt. On 7 December, after appointing Holden as chairman and Hayes secretary, the committee began its desperate bit to raise funds.

The club sold its best players and launched fundraising concerts. But as gates tumbled the financial situation just got worse.

So in March 1894 Holden, Hayes, Strachan and Prowse all resigned from the club’s committee. They had joined forces with pub landlord John Chapman, who had been involved with the club since 1889. That month they attended a meeting at Chapman’s Shakspere Hotel on Stockport Road (pictured below after its spelling had been changed).

Also present were Alfred Jones, Robert Heath, Frederick Skinner, Charles M'Laughlin and Edwin Hodson. The men were already well acquainted. Holden was a member of the pub’s bowling and angling committee, as were Heath, M’Laughlin and Hodson.

At the meeting it was decided to form a limited liability company to take over the running of the club. Chapman would be chairman, and Hayes secretary. Afterwards they approached the FA, and at the second meeting chose the name Manchester City.

The Ardwick committee was now led by Allison and Furniss. They also planned to form a limited liability company, but one that would run the club on amateur lines.

The battle lines were now drawn, and the key to victory was control of the Hyde Road ground, which had been rented on a short-term lease since 1887. As there was no available land in Ardwick, and finding a ground elsewhere and developing it was not a viable option for either party, whichever faction secured the lease would take control of the club. The other would perish.

On 4 April an application by Chapman’s group for affiliation to the Lancashire FA under the name Manchester City was rejected after the Ardwick committee officially opposed it. But the Lancashire FA informed them it would be accepted if they secured a ground.

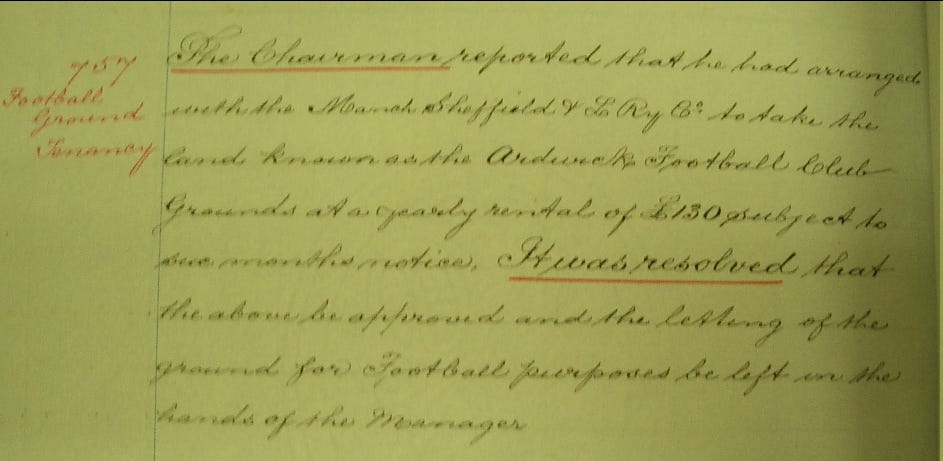

That month Chesters Brewery took over the Hyde Road lease after it had expired. It was then left to brewery manager William Cahill to decide which faction to sub-let it to.

On Friday 13 April, Cahill agreed to sub-let Hyde Road to Chapman’s group.

It wasn’t a surprising choice. Three members of Chapman’s group were involved in the drinks trade, including William Heywood, who was landlord of Chesters’ Junction Hotel on Hyde Road. As part of the deal, the brewery would later be given a 14.3% stake in the club as well as the exclusive rights to ‘supply all the wines, spirits, beers etc’ at the ground.

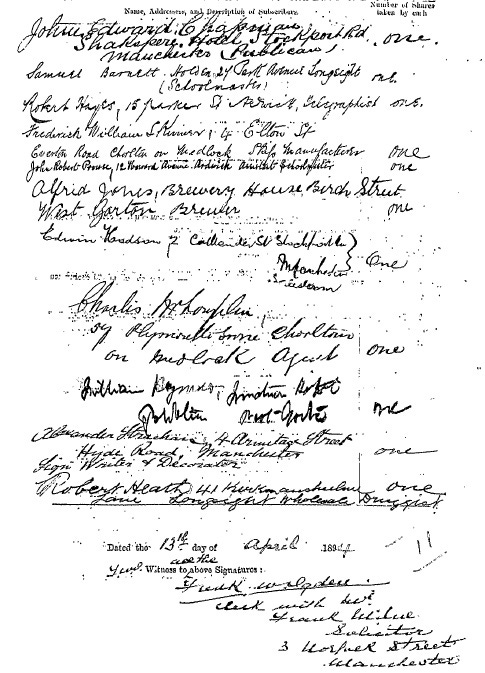

That evening, a triumphant Chapman presided over a meeting at the Octogon Congregational Schoolroom, Ardwick, where a motion to form The Manchester City Football Club Company Limited was passed unanimously.

Eleven £1 shares, out of its £2,000 share capital, were initially issued, and a Memorandum of Association signed.

The Ardwick committee immediately threw in the towel.

At a public meeting held on the Sunday it was announced that Allison’s faction had abandoned its opposition to the changes. The next day the new company was registered at Companies House.

After the application for affiliation to Lancashire FA was formally approved on 21 April, the Manchester City Football Club Company opened its subscription list. On 18 May, 700 £1 shares were issued.

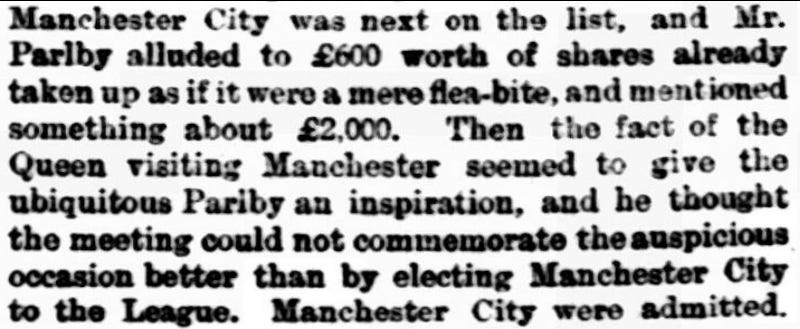

As the club had finished third from bottom of the Second Division, it was forced to apply for re-election at the Football League’s annual meeting on 21 May. Joshua Parlby, a seasoned political operator who had resigned as Ardwick secretary in March, represented City as their newly-appointed secretary.

With the club now debt-free and with £600 raised from the share issue (the brewery got theirs for free along with their exclusive rights), Parlby could now boast about the club’s healthy finances.

With a proven fanbase and large ground—and the backing of a giant brewery—City comfortably retained their League status.

The new legal structure did mean the club no longer held the players’ registrations. But it only cost £250 for Parlby, a former cattle trader, to put a squad together that summer. City even had enough money for ground improvements. On 15 August it was announced that,

‘the running track has been done away with and the playing portion enclosed with wooden railings, which will effectively prevent anyone encroaching on the field of play. The portion allotted to the spectators has been banked up all round, and will compare very favourably with the grounds of other League clubs.’

The running track was probably something Allison—who organised athletics events at the ground—and Chapman had been arguing about since it was installed in 1890. But with Hyde Road’s capacity now increased from 11,000 to 15,000, and with the League raising the minimum entrance fee for the 1894-95 season from 3d to 6d, the club’s new owners were looking forward to bumper profits.

So was City a new club?

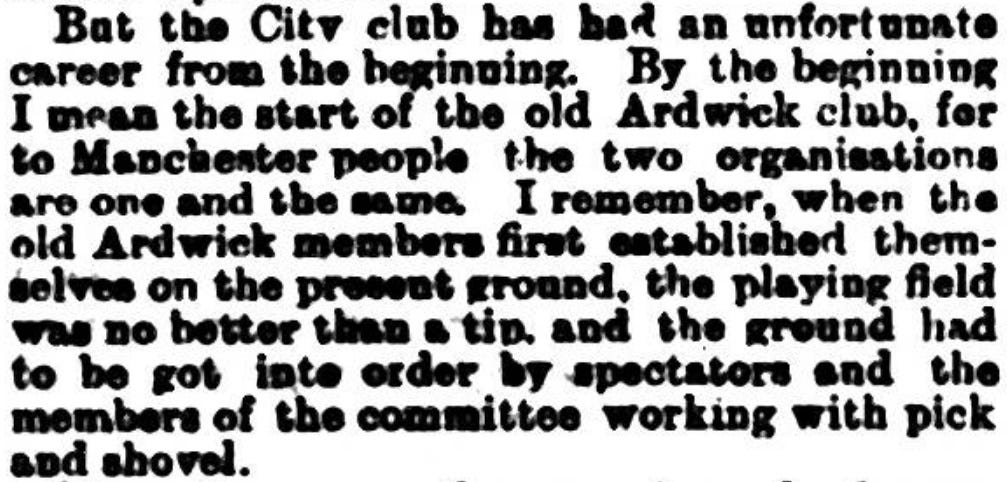

On paper, yes. In the same way that Rangers was a new club on paper in 2012. But no Rangers fans would argue their club was only 11 years old. And the United fans who proudly display their Norwich scarves would certainly not date their club’s origins to 1902, when the creation of a new ownership structure resulted in a change of name (and the removal of their ground’s running track).

At the start of the 1894-95 season, the same fans went to the same ground to watch a team managed by the same man. Their Hyde Road club was run, in the main, by the same people with financial ties to the same brewery.

As The Umpire, a sporting newspaper published in Manchester, explained: ‘the two organisations are one and the same’.

It was just a different shade of blue.

The best way to make sure you don’t miss anything is to subscribe for free below and have stories sent straight to your inbox. Paywalls, like any sort of wall, keep people out. I want very much to keep this work available to everyone but I also need to make a living. If you can, please consider supporting my work with one of the voluntary subscription options.

Or if you want to help out with a one-off donation you can Buy Me A Coffee.

You can also follow me on Twitter here.

Thank you for a well written article on a subject I have often thought about.

However, I have read that Furniss paid the club's debt and thus had to postpone his wedding? Is it a myth? Or where does that come into the picture?

On 26 April 1894 the Sheffield Evening Telegraph ran article that stated:

I notice that the prospectus of the Manchester City Football Club is out. From one which I received yesterday, I find rather a significant sentence:- "The management of this company is in the hands of directors who have not been officially connected with the Ardwick Football Club."

As I see it, Manchester City is more like AFC Wimbledon as both Ardwick and Manchester City existed at the same time in the same manner that Wimbledon and AFC Wimbledon did, and Manchester City and AFC Wimbledon have catfished Ardwick's and Wimbledon's previous history.