The Peter Swales Years (Pt 1)

1. The Ghost of Malcolm Allison

Six weeks after becoming chairman, Peter Swales lost his first manager. However, on this occasion he was not to blame.

On 17 November 1973, Johnny Hart resigned as City’s manager.

He'd only been in the job since March, following the departure of Malcolm Allison. But the 44-year-old was secretly battling serious health issues at the time, and only accepted his elevation from the coaching staff “because I didn't want anyone thinking that I didn't have the guts to have a go at it.”

In December 1972 Hart had undergone major spinal surgery which resulted in two discs being removed and a graft made from his hip. It had left him with severe numbness.

Worse still, he had been suffering from severe anxiety and depression. It had been a problem since his playing days, in which he made 178 appearances for City and scored 73 times. During one period where he was struggling with form, Hart wore earplugs during games to block out the barracking from the crowd.

Shortly after becoming manager, Hart was left with 'no feeling at all down the left-hand side' of his body. His mental heath also rapidly deteriorated.

On 26 October, Hart had a nervous breakdown. He was only able to formally resign after sixteen days of recuperation in hospital.

Five days after his departure, he was replaced by Ron Saunders, who had been the Norwich manager since 1969. Former captain Tony Book, who had been acting as caretaker manager, became his assistant.

At Norwich, Saunders had 'performed little short of a miracle on a diet of limited cash and an abundance of hard work.' After turning them into 'one of the fittest sides in the country', Norwich won the Second Division title in 1972. Saunders had kept them up in their first ever season in the top flight and led them to a League Cup final.

But he was well aware that he had joined a very different type of City. On the day of his appointment he told the Daily Mirror,

“When I was joining City some friends warned me: “The ghost of Malcolm Allison is still at Maine Road. Well, I know what an impact Big Mal has had on the game. But I don't believe in ghosts.”

A month older than Swales, the 41-year-old Saunders had also spent his two years National Service in the Royal Army Service Corps. But while Swales was breaking the rules by renting radios to his fellow servicemen at a 100% mark-up, Saunders was enforcing them as a military police officer.

At Norwich he had introduced one of the 'toughest training schedules' in football. The City players were familiar with punishing fitness regimes. Joe Lancaster, the former athlete who Allison had appointed fitness coach in 1967, was referred to on the training ground as “Adolf”. But Lancaster’s grueling workouts were usually tempered with Allison’s words of encouragement.

Saunders, however, brought what Book described as a “sergeant-major approach” to City’s training. According to Alec Johnson’s The Battle For Manchester City,

'He quickly began to upset both players and staff alike by his brusque style. 'He was a bit of a dictator as far as we were concerned,' says former skipper Ken Barnes, then a coach at Maine Road.

Many players recall Saunders standing behind them and asking if he was hurting them. When they replied 'No' Saunders told them, 'Well I should be, because I am standing on your hair. Get it cut.’'

The 33-year-old Denis Law, who Hart had signed on a free transfer in July after he had been released by United, was soon his primary target. His form at City had been disappointing. On 19 November, the Daily Mirror's Frank McGhee commented,

'No player, however great his reputation, has the right to husband his remaining resources in such miserly fashion and dish up such a meagre portion to a playing public as Law did in this game.'

Saunders’ way of dealing with Law's loss of form was to have the player 'acting almost as a ballboy at the back of goal during training games’.

According to Johnson,

'For the rest of the players and staff to see such treatment of a player who had become a legend in his own lifetime and who was revered in both United and City camps was embarrassing.'

However, some of the younger players did respond positively to the new hard-line approach. On 30 January, City reached the League Cup final after beating Plymouth over two legs. They'd benefited from a favourable draw, beating Walsall, Carlisle, York and Coventry in earlier rounds. But in the final on 2 March, defeat to Wolves brought City's run of four successive wins in major finals to an end.

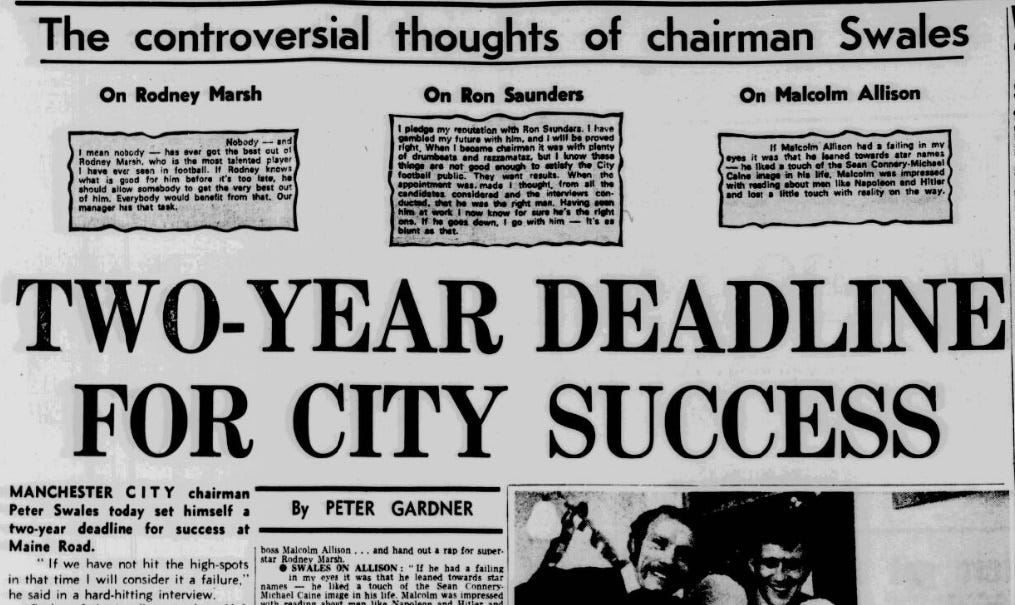

In December 1973, Swales had set himself a two-year deadline for success.

On 12 March, City signalled their intent by beating Liverpool and 1972 title winners Derby to the signing of England forward Dennis Tueart, a key member of Sunderland’s 1973 FA Cup-winning side.

The 24-year-old Tueart was valued at £275,000 in an exchange deal that saw Sunderland’s 21-year-old midfielder Mick Horswill arrive and England under-23 defender Tony Towers go the other way.

Towers, another product of Harry Godwin's youth team production line, was valued at £115,000 in the deal. Added to the £100,000 that City had received for 22-year-old defender Derek Jeffries in September 1973, it meant that the capture of one of England's brightest young stars had effectively only cost the club £60,000.

Swales declared:

'This is only the start. We want to build up Manchester City until we become the best team in the land. We cannot guarantee that but we are making the effort. This is not the end of the spending—and has not put us into debt.”

Despite City’s indifferent league form, attendances were still holding up. And with healthy finances bolstered by a successful youth policy, Swales’ optimism was looking well-placed.

However, Saunders was about to discover that City's training pitch was a very different place to a 1950s parade ground.

City have notched up a remarkable series of firsts throughout its history, though not all of them are ones the club would want to highlight on social media.

In the wake of the League Cup final defeat, City provided what might be the very first example of “player power” in football.

Players had become increasingly well paid following the scrapping of the maximum wage in 1961. As a result, some had developed business interests outside of football whilst still playing. Others had their own newspaper columns where they were encouraged to be as outspoken as possible.

By 1974, no player represented this new-found freedom more than 29-year-old Francis Lee. Now a Daily Mirror columnist and the owner of a thriving paper recycling business, Lee also had the backing of outspoken 31-year-old Mike Summerbee, who owned a successful men's outfitters.

With their discontent seeming to seep through the team, City earned just one win and three draws in eight league games.

Saunders' response was to attempt to transfer Lee to Birmingham, Summerbee to Leeds, and Law to Motherwell. Although an £80,000 fee was agreed with Birmingham for Lee, the player refused the move.

After a 3-0 defeat at fifth-placed QPR on 9 April, the Manchester Evening News declared: ‘City Hit Crisis'. According to reporter Peter Gardner,

'Manchester City in their present mood will not win another game this season. They could even finish that losing streak in the Second Division... so bad is current form.

Queens Park Rangers cakewalked the game 3-0... and it could easily have been double that margin as City showed a couldn't-care-less approach.

There is little fight, spirit is virtually non-existent, and one of the most loyal players said: “We no longer have the good of the club at heart.”

Clearly the mood is verging on a revolt.'

An unnamed player, who sounded suspiciously like Lee, declared: “We are a family team, and when one person is smacked the others are hurt and cry.”

The paper also reported that Saunders,

'Did not, however, travel back with the team today, going on to his Norwich home.

Assistant manager Tony Book, who was left in charge of the party, was met on his return at Piccadilly Station by director Ian Niven and taken straight to a meeting at Maine Road.'

On Thursday 11th, the board decided to act. According to Johnson,

'The City chairman and two other directors decided to hold court in the players' lounge. One by one the players were called into the room and asked to give their opinion of the manager. Not just the first team but some of the young reserve team players were also spoken to by the directors.'

At a board meeting later that day, City’s directors voted to sack their manager.

Saunders only received the news after being summoned to Swales' Altrincham house at eight o'clock the next morning. He later recalled,

'He told me he had decided he had to dismiss me. I was stunned. Yet, looking back, not surprised. For that short time at Maine Road, nothing could really surprise me.

But when Swales told me I was finished after such a short time and after having brought me in to sort things out MY way, I was just completely baffled by the man. And what he said next left me even more nonplussed. He said, “I am probably making the biggest mistake of my life in dismissing you and I know it.”’

“I'm pig sick about the whole business,” Saunders told the Liverpool Daily Post. “I've worked in close harmony with the chairman and the board—and everything I did at Maine Road was with their backing and co-operation until the last few days.”

He told the Evening News,

“There were so many people interfering and trying to influence things, you never knew what was coming next.”

Swales responded:

“What Ron says is fair comment. But he must agree he never had any interference from me.”

He was probably telling the truth. As successive City managers appointed by Swales have testified, he rarely interfered in team affairs.

More likely, it was the club’s fractured shareholding that led to Saunders’ demise.

City’s board and shareholdings, April 1974

Chairman: Peter Swales (11.5%)

Vice-chairman: Simon Cussons (10.5%)

President: Joe Smith (31.0%)

Directors: Eric Alexander (18.3%), John Humphreys (1.7%), Sidney Rose (0.7%), Robert Harris (0.1%), Ian Niven (0.8%), Chris Muir (0.7%)

Joe Smith had once called Allison “the greatest man in football”, and had the shares to forge the boardroom alliances that could bring about his return. Allison’s “fan club” also included Ian Niven, who had introduced Smith to his hero, and Chris Muir.

Saunders’ friends were right: the ghost of Malcolm Allison was still at Maine Road.

Earlier that season Swales had declared in the match programme: ”If he (Saunders) goes down, I go with him.” Three days after Saunders’ departure, Swales received the dreaded vote of confidence from his fellow board members.

The views of the club’s president were not offered to the Evening News. But Swales knew that his position was now under threat.

Although he occupied the throne, Smith was still the king-maker at City.

Next Saturday I’ll be examining another era of City’s history with a piece entitled: The Greatest City Chairman You’ve Never Heard Of.

But let’s not just look back. We’re now witnessing the greatest era in City’s history. So each Wednesday this Substack will be devoted to City’s present—both the serious and quirky. This week: Pep’s Wheel of Justice.

And because we have ‘istory, City also have a mountain of fantastic photos. Join me on Twitter where I’ll be posting historic images each day, many that have not been seen before. No angry Twitter rows, just great photos. And maybe the occasional piss-take.

The best way to make sure you don’t miss anything is to subscribe for free below and have stories sent straight to your inbox. Paywalls, like any sort of wall, keep people out. I want very much to keep this work available to everyone but I also need to make a living. If you can, please consider supporting my work with one of the voluntary subscription options.

Lastly, my girlfriend says I need to keep flogging my books or she’ll flog me. So, here they are.