The Greatest City Chairman You’ve Never Heard Of

One of the most striking things about the history of Manchester City is that, until recent times, we’d won surprisingly few trophies for a club of our size. Throughout most of the 20th century City had one of the largest fanbases in British football, and from 1923, the largest stadium in English club football.

For large parts of our history City could be likened to a Ferrari stuck in first gear. And never is that better illustrated than in the stories of the Smiths. No, not them. I’m referring to the two City chairman named Smith: Bob, the man who kept the club in first gear, and Walter (no relation), the chairman who, for two glorious years, showed just how fast this formidable machine could go.

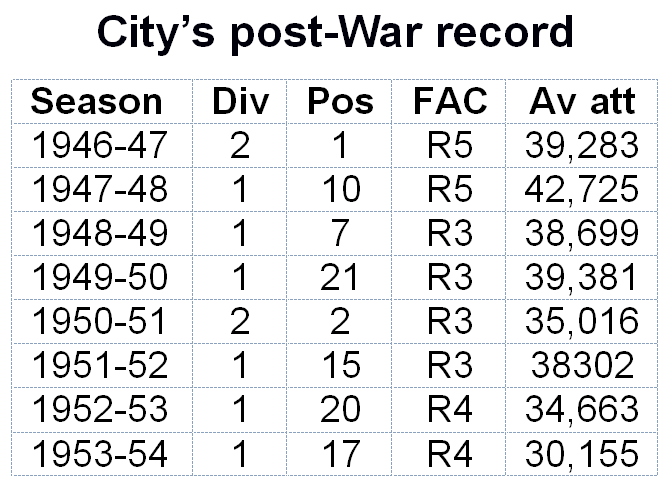

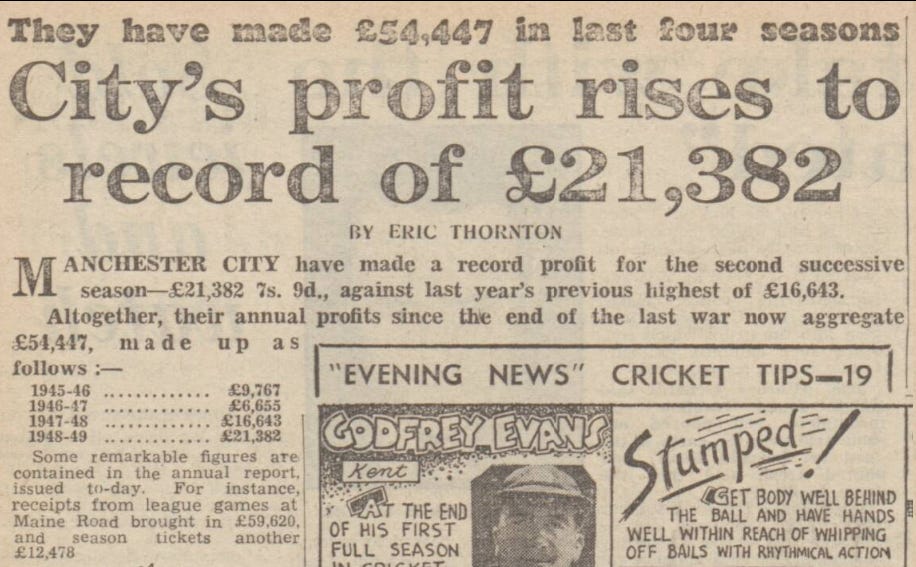

The post-War period under Bob Smith’s chairmanship was a dismal one for City. In the eight seasons following the resumption of league football after the War, the club recorded an average 17th place finish. City also failed to win a solitary FA Cup game for four consecutive seasons between 1948 and 1952, while average attendances plummeted from a high of 42,725 in 1947-48 to just 30,155 in 1953-54.

Yet throughout this period the club posted record profits.

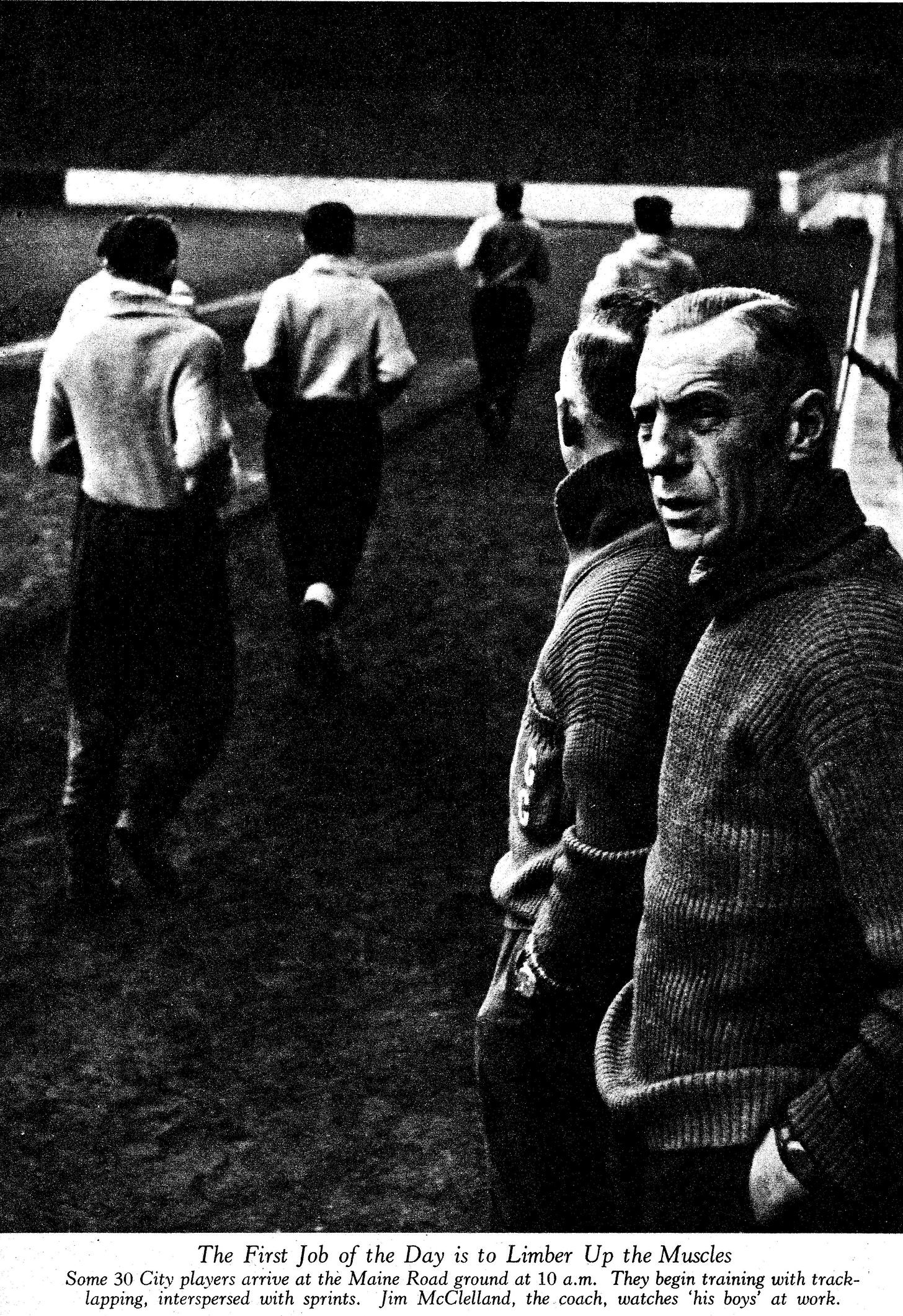

Where that money was being spent was something of a mystery. City had no training ground, with laps around the Maine Road pitch and head tennis on the concrete car park behind the Platt Lane stand being deemed sufficient. The ground had no physio room. Not that one was needed as the club didn’t employ a physiotherapist.

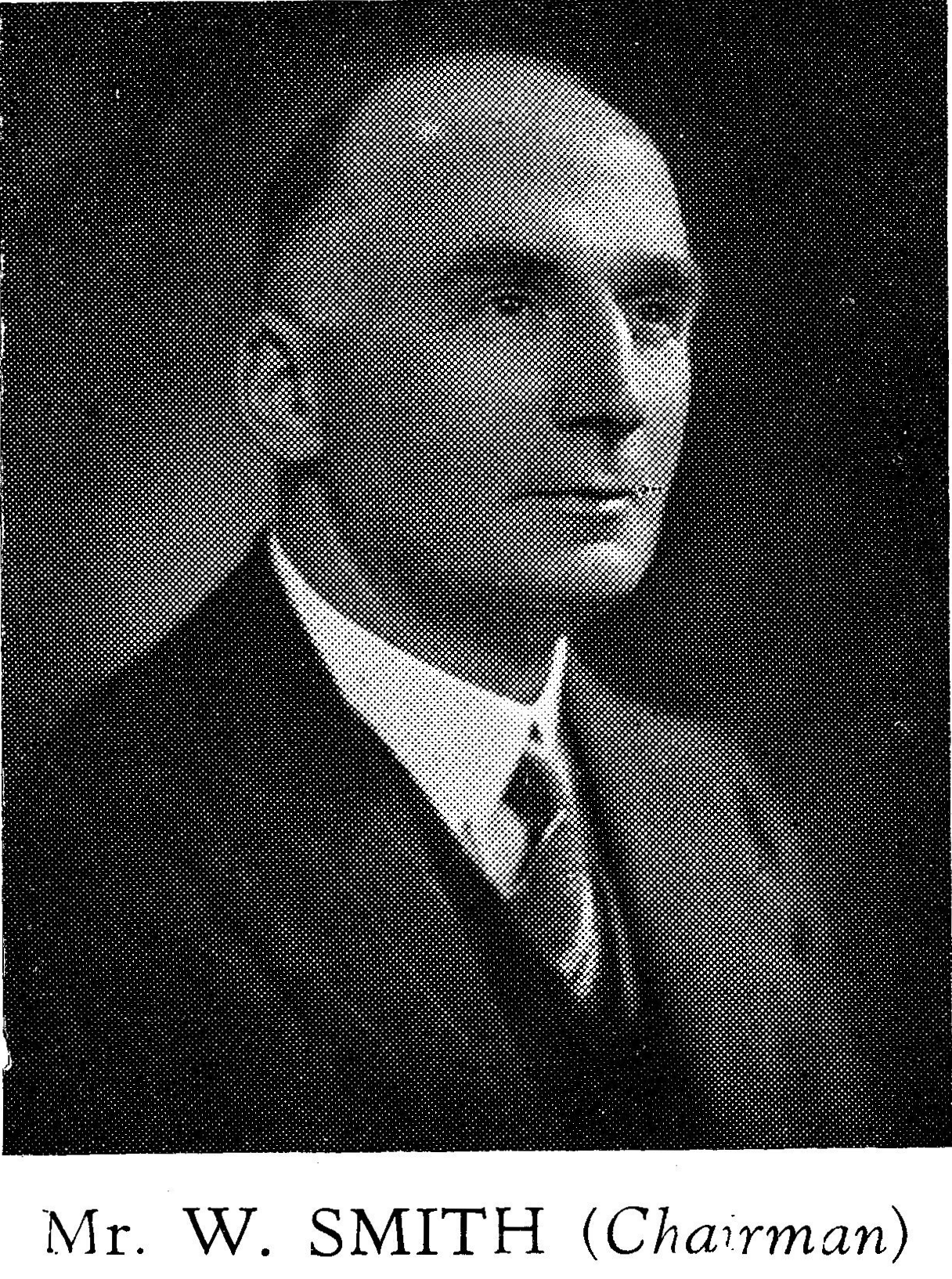

But in the summer 1954, 80-year-old Bob Smith finally stood down. His replacement, 65-year-old Walter Smith, was to prove a very different figure from his namesake.

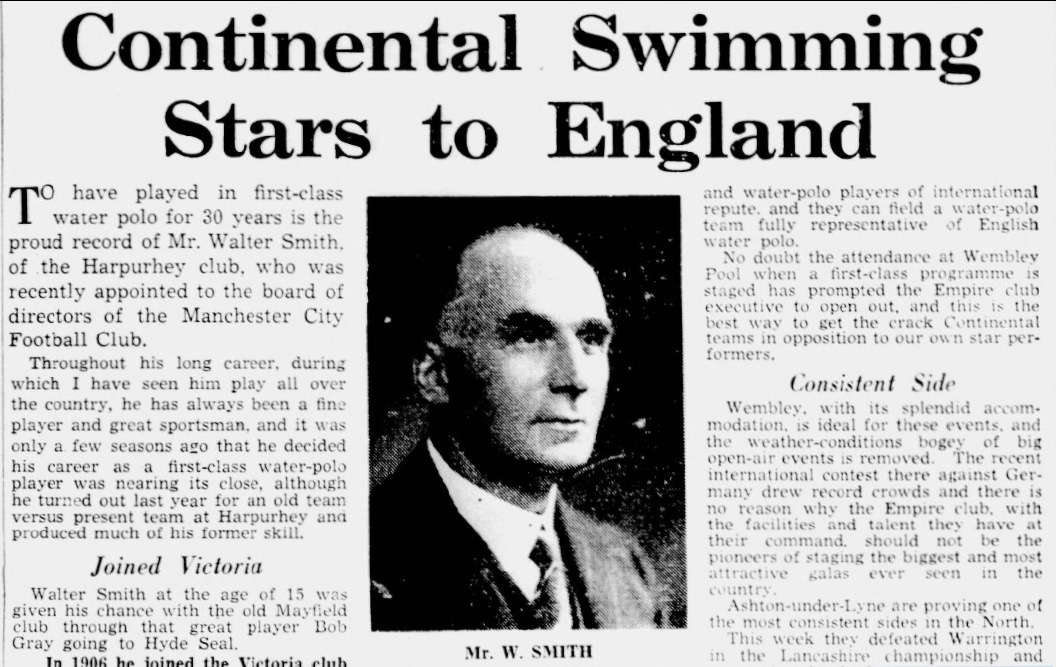

Originally a bricklayer, Smith became a partner in “one of the most prosperous” building firms in Manchester, G & W Smith Ltd. He had joined the City board 1937 as a member of the City Shareholders’ Association, an organization once controlled by the legendary former chairmen John Allison and Lawrence Furniss. And like his predecessors, Walter Smith wasted no time implementing change.

He knew all about the importance of fitness, having played first-class water polo for 30 years from the age of 15. In 1934 he joined Harpurhey, and captained the side that won every trophy except the National title.

That summer a large gymnasium was built under the main stand. A physiotherapist, John Beeston, was appointed, and a physio room was built for him.

City’s first official handbook was launched, allowing fans to see the faces of the men running the club for the first time.

Smith also took the unusual step of dividing the role of club secretary into two positions. Les McDowall was given the title of manager and became responsible only for footballing matters, while his assistant, Walter Griffiths, was put in charge of the day-to-day club business. The move allowed new tactical ideas to flourish, including the use of a false number nine that became known as the “Revie Plan”.

Although it was assumed at the time that City were merely copying the Hungarian tactics used in their 6-3 defeat of England at Wembley in November 1953, according to the Ken Barnes’ biography, This Simple Game, the system had actually been developed in City’s reserve side months earlier. “It had fuck all to do with the Hungarians,” said Barnes, who played in both Cup finals.

The changes produced instant results. City reached the FA Cup final in May 1955 and finished seventh in the League. Don Revie, whom Smith had played a key role in signing in 1951, was named Footballer of the Year. The Daily Mirror described the “Revie Plan” as ‘the greatest advancement in modern soccer’ (though the Birmingham Daily Gazette called it ‘over-rated’).

City’s Cup run, and an increase in average attendances from 30,200 to 35,200, boosted the club’s spending power. In the summer of 1955, forward Bobby Johnstone, arguably the most skilful player of his generation, signed for £22,000.

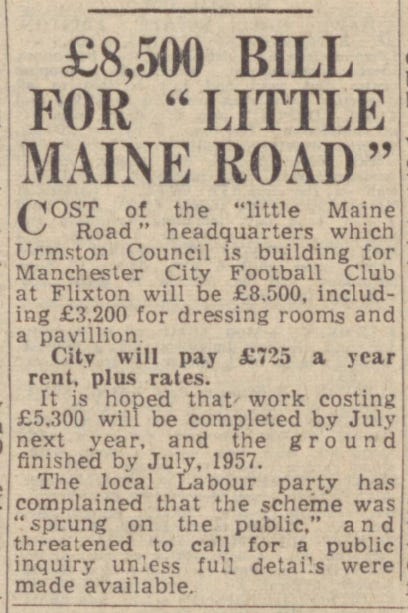

In November, the long search for a training ground ended after a site was acquired in Shawe View, Flixton.

City finished fourth in League in 1955-56 season, the highest placing since 1937. A week later, Smith’s hard work and planning got the glory it deserved.

Smith had played in two of the three National finals that Harpurhey had lost over a four-year period. But on 5 May 1956 he finally helped secure a national trophy after City returned to Wembley to win the FA Cup.

It became known as the “Trautmann Final”, after the player that Smith was instrumental in signing. Smith was also responsible for the signing of Cup final captain Roy Paul in 1949, while in 1953 he flew to Ireland ‘to beat half a dozen clubs in a dramatic night signing’ of forward Billy McAdams (who couldn’t play for his first two seasons at City due to a serious back injury).

City had also introduced a voucher scheme in the match-day programme that season, ensuring that it was the most loyal of City fans who watched them lift the trophy.

Despite the extra spending, City still managed to post profits of £9,767 for the 1955-56 season. The only disappointment was a dip in average attendances to 32,198, the result of the most severe winter that century. More than half of Maine Road was still uncovered, so during the 1955-56 season the club drew up plans to roof the Popular Side. Renamed the Kippax after its completion the following autumn, it meant that a record 52,000 fans, from Maine Road's 77,000 capacity, could now be under cover.

Smith had been too ill to attend the FA Cup final. Shortly afterwards, he was replaced as chairman by Bob Smith’s son-in-law, Alan Douglas. Walter Smith died in January 1961, aged 72. Six days earlier City was beaten 5-1 by United at Old Trafford, part of a run of nine defeats in ten games. How much better City’s fortunes would have been if Walter had enjoyed better health can only be imagined.

While we like to talk about City’s unsung heroes on the pitch, sometimes it’s the person in the chairman’s seat who is just as deserving of the accolades. Thanks to Walter Smith, City fans have admired the artistry of the Revie Plan, the brilliance of Bobby Johnstone, and the Cup final heroics of Bert Trautmann. And thanks to him we had a magical place called the Kippax.

He was one of City’s greatest unsung heroes.

My new book, 50 Important Questions About Manchester City F.C Answered, is now available on Amazon here, priced £12.95.

I do want to keep this Substack free to read. So if you like my work, buying my books is a great way of supporting it. Plus, I think you’ll really enjoy this one.

I hope it will provide the answers you’re looking for.

My book on City’s origins is available on Amazon here.

The best way to make sure you don’t miss anything is to subscribe for free below and have stories sent straight to your inbox. Paywalls, like any sort of wall, keep people out. I want very much to keep this work available to everyone but I also need to make a living. If you can, please consider supporting my work with one of the voluntary subscription options.

On Mondays, paid subscribers will receive an exclusive weekly story in their inbox. These will reveal some of the dodgy things I’ve experienced while working in national newspapers (and believe me, some of them are really dodgy). I’ll also be sharing some of the things I’ve discovered about City’s past that are best not posted publicly.

Each month there will be two other stories only available to paid subscribers.

Or if you want to help out with a one-off donation you can Buy Me A Coffee.