How Peter Swales became City chairman (Pt 9)

9. Last of the Alexanders

Catch up with the earlier parts of this story here:

The involvement of the Alexander family in Manchester City goes back to the very time the name was adopted.

In 1894, the 27-year-old Albert Edward Burns Alexander was elected to the club's ground committee, shortly after City had transitioned from a members' club to a private limited company and ditched the name Ardwick.

In 1907, he inherited the carriage company that bore the family name. The thriving business, 'which included 60 horses and dozens of four-wheeled cabs', enabled him to buy shares in both of Manchester's football clubs. He rarely found time to watch games, as on Saturdays he 'took the reins himself' in order to 'drive visiting football teams to the City or United grounds'.

In 1911 he became a City director, and by 1935 had risen to the position of vice-chairman. In later life the press called him a “G.O.M (Grand Old Man) of football”, while one journalist referred to him as City “royalty”. However, during his time as City vice-chairman and later president, which ended with his death in 1953, City were relegated twice and reached a solitary FA Cup quarter-final.

His son, Albert Victor Alexander, deserved every accolade that came his way. In just seven years as chairman he had turned City—once again—into one of the most successful clubs in football before passing the reins to his only living son.

Eric Alexander had also been christened Albert but had instead opted for his middle name. His formative years could not have been more different from his war veteran father. Growing up, he met royalty, presidents, prime ministers, and tribal chiefs. By the age of twelve he was fluent in French, which he put to use during his month-long summer holidays in the Alps.

At 19 he became the youngest member of the City 'A' team his father had set up. His dream was to become a professional golfer or footballer. But in 1955, after studying art at Manchester University, he instead joined the marketing department of National Coal Board as a graphic artist.

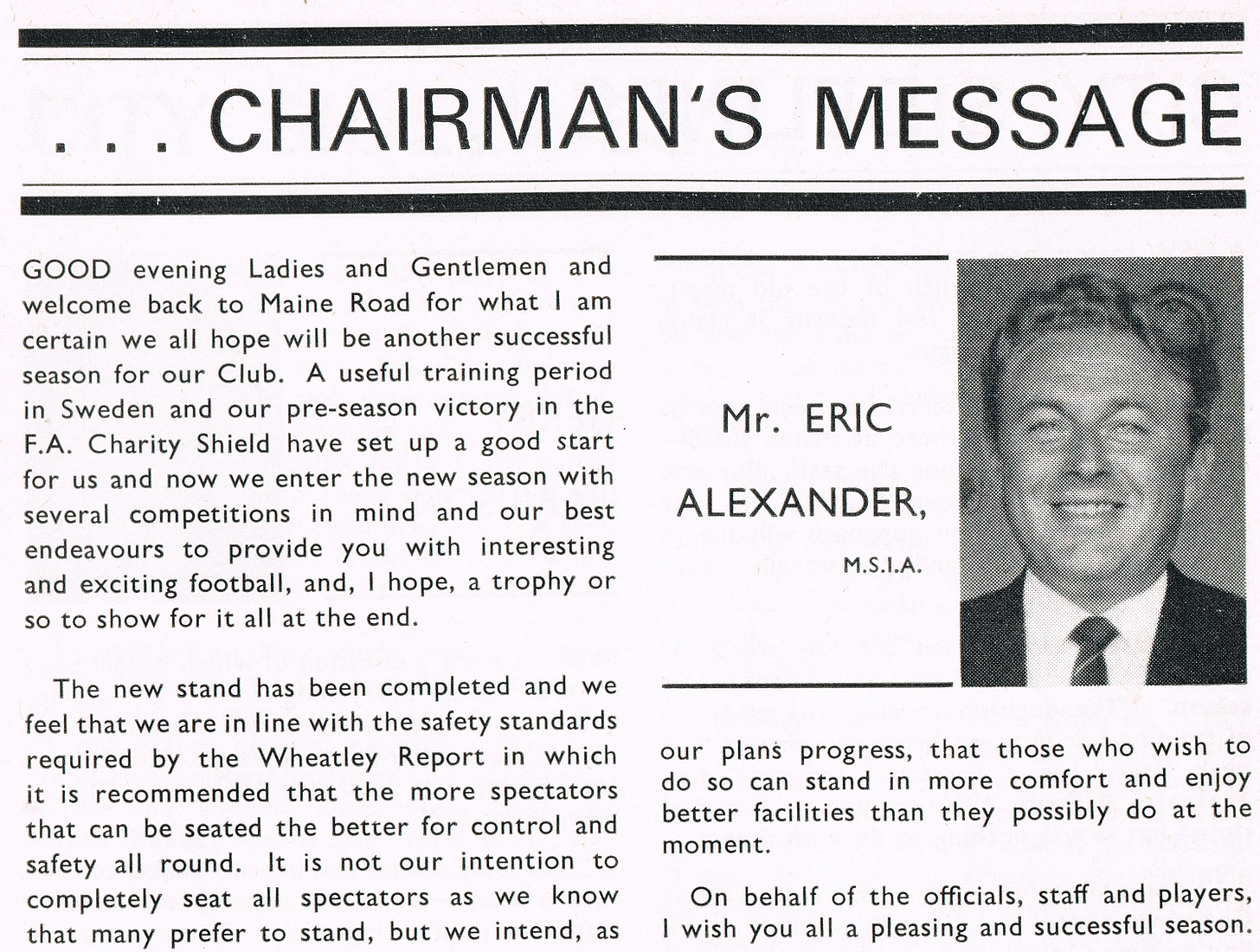

He was still at the Coal Board when he was appointed a City director in 1968, aged 35. His oversaw the 'youth set-up, training facilities and Maine Road pitch', and had passed an FA coaching course by the time he was made chairman in November 1971.

But the one area in which he hadn't received any training was in running a business, something that became obvious to Malcolm Allison following the signing of Rodney Marsh in March 1972. In Colours of My Life he recalled:

'I had agreed £180,000 with Jim Gregory, the Rangers Chairman, but he only needed 10 minutes with Joe Smith and another director, Eric Alexander, to push that up by another £20,000.'

Nor had life equipped him to steer his way through the boardroom politics of a large, thriving and complex business. And following the death of his father in September 1972, it was a path that Eric Alexander had to navigate alone.

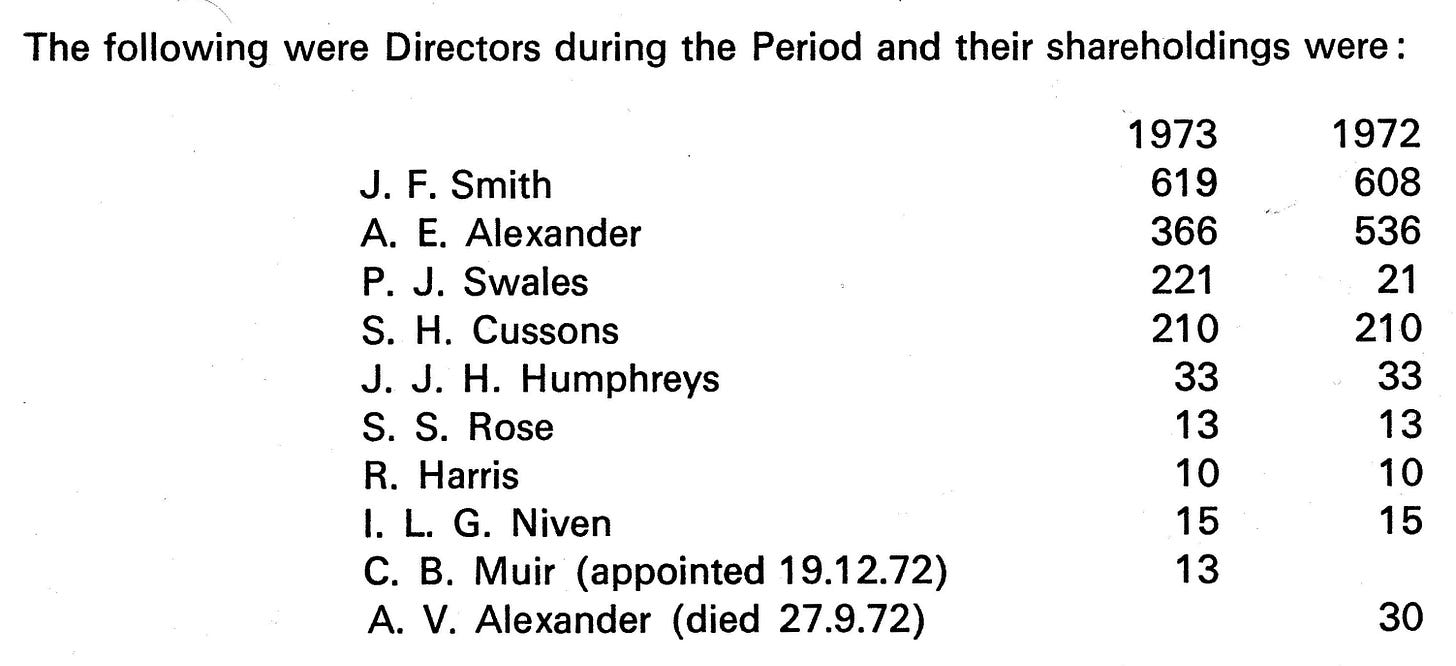

City’s board and shareholdings, September 1972

Chairman: Eric Alexander (28.3%)

Vice-chairman: Peter Swales (1.0%)

President: Joe Smith (31.0%)

Directors: John Humphreys (1.7%), Sidney Rose (0.7%), Robert Harris (0.1%), Simon Cussons (10.5%), Ian Niven (0.8%), Chris Muir (0.7%)

Eric appeared to approach the role as though he was in charge of a large social club. Not unlike Gatley Golf Club, in fact, where he was captain and held the course record. In his autobiography, Please May I Have My football Back?, he recalls:

'I had been giving some two or three hours a day to the job and thoroughly enjoying most of it. I would see the Secretary, look around the ground, talk with Stan Gibson, perhaps have a cup of tea with the laundry ladies, some of the unsung heroines of the Club and go to the training ground.’

There weren’t any more programme messages from the chairman, and throughout the season he often handed the role of club spokesman to his trusted vice-chairman, Peter Swales.

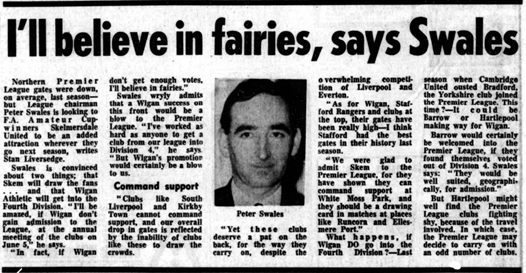

Swales had by now stepped down as chairman of Northern Premier League, but not before helping create non-League football’s showpiece Wembley event, the FA Challenge Trophy. That had generated goodwill from the FA. And now, with his role at City allowing him to forge ties with League club chairman, it was time to leverage his influence.

In July 1973 Swales was elected to football’s governing body, the FA Council.

Swales told the Manchester Evening News,

“I would like to thank Sir Matt Busby and the rest of the Manchester United directors for nominating me and I would also like to thank all the local clubs for their support.

He added:

The work will obviously take a certain amount of time, but it will not interfere with my commitments as a director of Manchester City.”

For once he was telling the truth. As Alexander later learned,

‘Peter Swales was after the Chairmanship from Day One that he became involved in Manchester City, although he was bright enough to bide his time.'

But there was another City director who had ambitions for a greater role: Simon Cussons, the managing director of the giant cosmetics company that bore his name.

His family background bore some similarities to the City chairman's.

His great-grandfather, Thomas Cussons, founded the company—coincidentally, in 1894—with his son, Alexander. Cussons, Son & Co soon expanded into a derelict mill in Kersal Moor, Salford, turning it into a 14-acre factory that made soap and talcum powder, cosmetics and perfumes.

Following Alexander Cussons’ death in 1951, the chairmanship passed to his son, Leslie. By the time of his death in 1963, Cussons Group Limited was valued at £8million (around £465million in today's money). Simon Cussons, one of Leslie's two surviving children, inherited a large stake in the company, as well as his share of large landholdings in Cheshire, Derbyshire and the Isle of Man (the Cussons Family Trust also owned at least 65,000 acres of land in Scotland).

Simon had been a City fan since his father first took him to a game aged five, he later told CheshireLive. In 1964, aged 21, he bought a 10% stake in City for just £5,000. “The guy who was next to me at the games was buying a stake. The idea appealed to me so I just went for it,” he said.

After joining Peter Donoghue’s takeover consortium, he’d gained his a seat on the City board at the Midland Hotel meeting in June 1971 that Swales had brokered. At the meeting, it appears that an agreement was also made for Eric Alexander to succeed his father as chairman. For that agreement to work, it's likely that Joe Smith had promised not to use his large block of shares to unseat him.

But in the summer of 1973, an opportunity would present itself for Swales and Cussons to advance each other’s interests.

The reason was that Eric Alexander desperately needed cash.

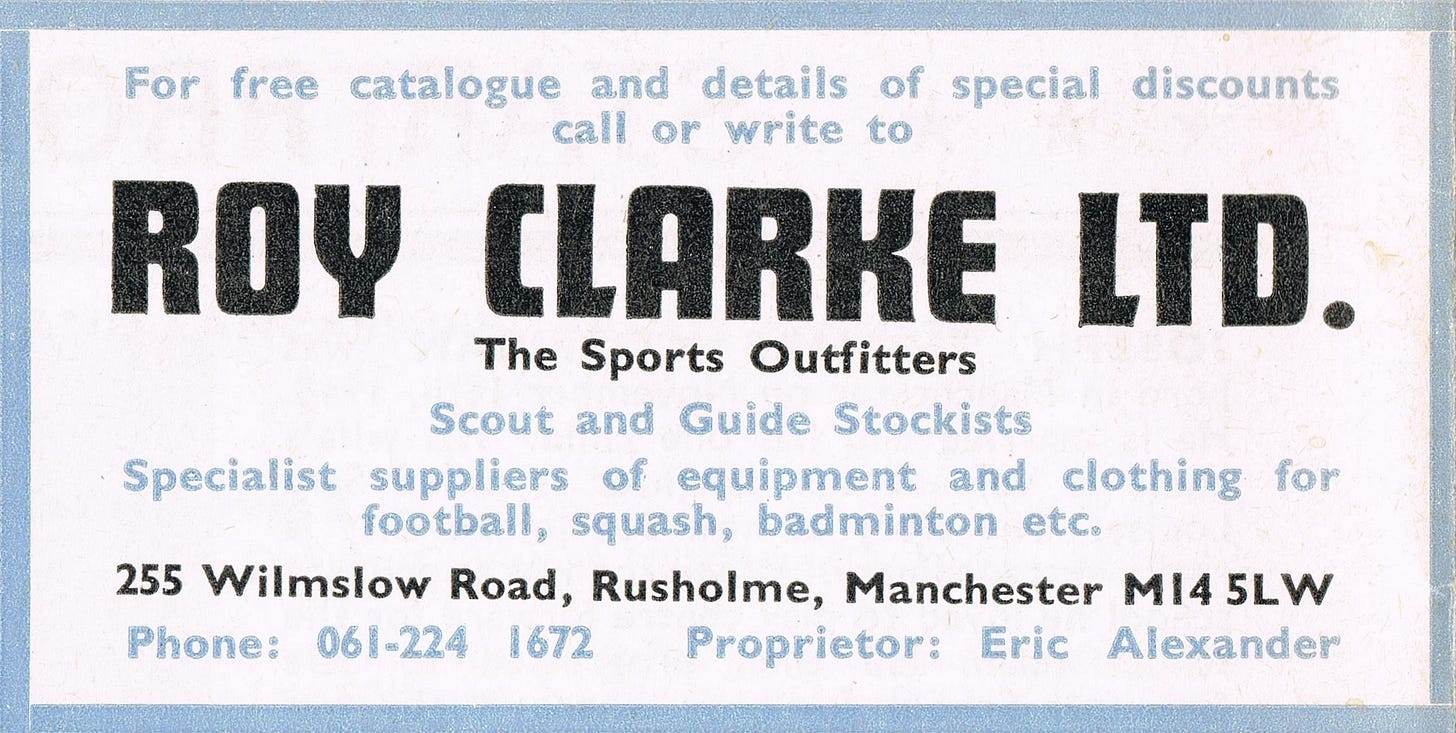

After becoming chairman, Alexander had left the Coal Board to take a contract with a Manchester advertising company. He quit less than a year later following an 'incident' with the company's chairman in the Midland Hotel restaurant. Around this time he bought a sports shop in Rusholme from former player Roy Clarke, the manager of City's thriving social club.

The timing couldn’t have been worse. Supermarkets and chain stores were by then bulk-buying sports goods and selling them at a price that smaller shops were buying them for. To make matters worse, the middle-class flight to the suburbs that had begun in the 1950s was also affecting sales. The business, Alexander admitted, 'was starting to suffer’.

Although City now had an annual turnover close to £1million, that money was out of Alexander’s reach. FA rules did not allow club directors to be paid, and with annual dividends to shareholders limited to 7.5% of the nominal share value, the maximum he could earn on his 566 £1 shares was just £42 a year.

It’s unclear exactly when, but in the summer of 1973 Alexander struck a deal that would haunt him for the rest of his life.

Believing that Swales was his ally against the takeover group, Alexander sold him 200 of his 566 shares, representing 10% of the club. It’s unclear how much he got for them. Smith had paid £216 a share for Johnson’s 25% stake in 1971, which would value Alexander’s 200 shares at £43,000. He probably would have received more than that—although, given his head for business, it’s also possible he didn’t.

It wasn’t long before Alexander realised his mistake. As he later remarked, 'Swales had been running with the hares and hunting with the hounds.’

With Swales and Cussons now controlling 22% to Alexander's 18.3%, he was powerless to prevent his removal. On 16 August, Alexander informed shareholders that he would be standing down as chairman at the Annual General Meeting on 5 October. Swales would be the new chairman, while 30-year-old Cussons would become vice-chairman.

Alexander didn’t mention the share sale in his autobiography, so it’s unclear exactly what events took place to prompt his resignation. But the explanation he gave to the Manchester Evening News was hardly convincing:

“The time for change is ripe. I am stepping down for personal as well as business reasons. I have spent a lot of time and effort as chairman these past two years and this has been to the detriment of my family.

I feel I want to shy away from any position of responsibility for a time.”

There’s an old saying in Lancashire: “Clogs to clogs in three generations.” While the third generation of Alexander at City was never in danger of ending up broke (his shares in United saw to that), the adage may still be apt.

The Victorian AEB Alexander, who for decades grafted to build up a successful business, plotted and battled for power at a great football club, passed it on to his son, who passed it on to his—who traded it for a sports shop.

The chairman’s job was one that “should be passed around providing there are suitable men”, Alexander told the Evening News that day.

But Swales only played for keeps. And with Alexander now sidelined, he quickly made sure his new vice-chairman was playing ball.

“I never saw it as a business. For me it was an enjoyment,” Cussons later recalled. Following his promotion, Swales gifted Cussons a new hobbyhorse, a column in the match programme where he could expound his many views on the future of football.

Swales had offered an upbeat message on his first day as chairman-elect, telling the Evening News,

“City now have the potential to get right back to the top once more with the target Europe... and by that I mean the European Cup.”

But then, he said a lot of things.

According to the Evening News, the new City chairman had ‘his feet firmly on the ground’. Alexander, though, remembered differently:

'During the course of the first Board meeting at which Swales presided as Chairman, he lit a cigarette, unheard of during a meeting at that time, tilted back his chair, put his feet up on the table and crossed his legs.'

The Peter Swales era had now begun.

I hope you enjoyed this serialization. Next Saturday I’ll be starting The Peter Swales Years which, I hope, will explain exactly what happened during his 21 years as chairman. I’ll also be running stories each Wednesday covering City’s past, present and future.

And now it’s time to hold out a collection plate.

Although I eke a living as a writer, I want to keep most of the content on here freely available. But if you want to support my work, you can take out a voluntary paid subscription below. Any contribution will be greatly appreciated.

Paying subscribers will receive exclusive stories based on my latest research.

I’m going to be revealing some truly remarkable things about this club’s history, solving a few long-standing mysteries, and exploring some aspects of Pep’s City you might find interesting.

As a former journalist, I’ll also be explaining why modern-day sports media is so dreadful. And if I get drunk enough, I might tell you a few secrets about Piers Morgan.

Excellent insight into the running of city and the political shenanigans that went on behind the scenes . Very interesting and well written