How Peter Swales became City chairman (Pt 6)

6. Out with the Old

By the spring of 1971, the seven-year battle for control of Manchester City was finally taking its toll on the 79-year-old chairman, Albert Alexander.

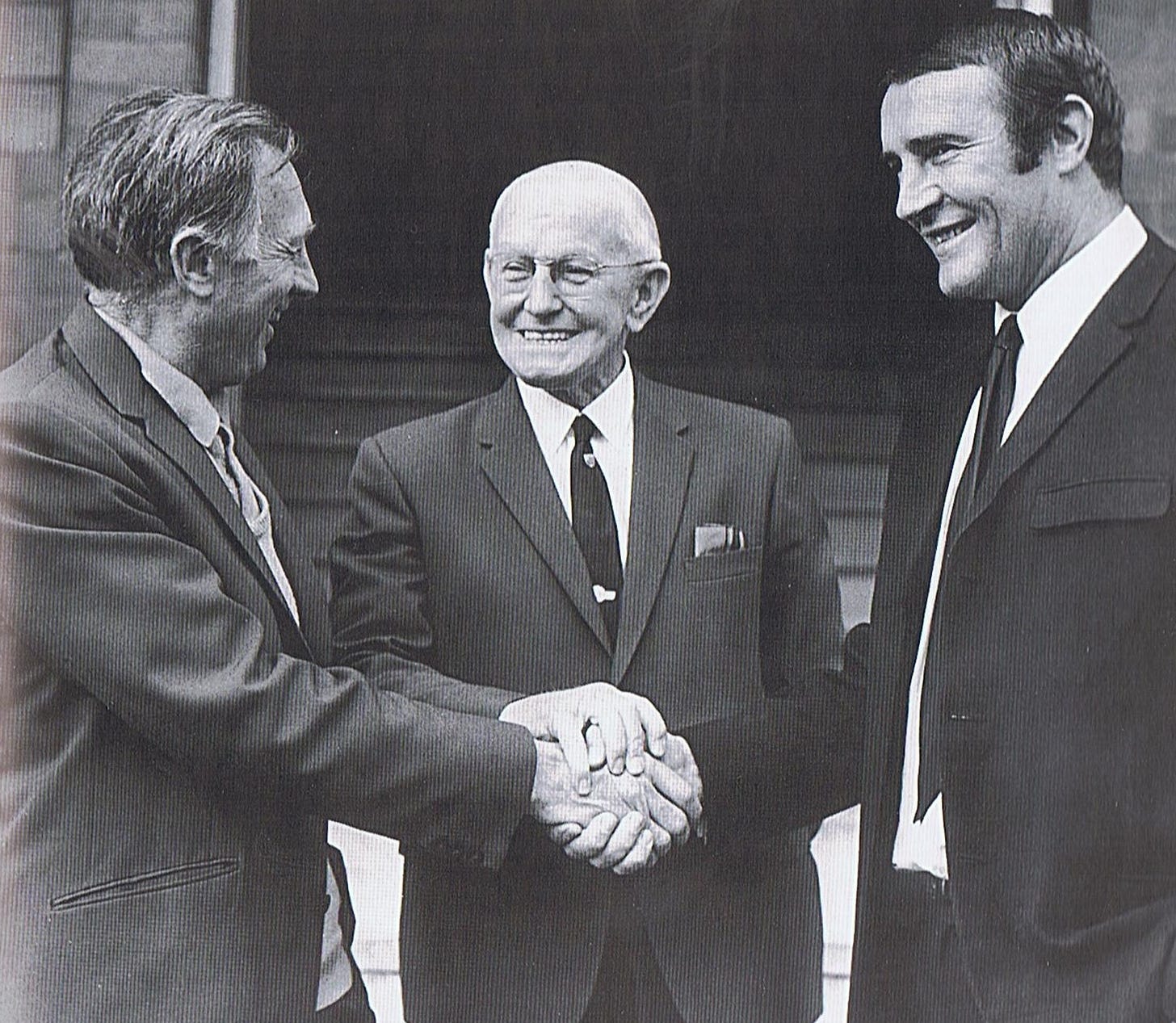

With legal bills ‘mounting alarmingly’, he now turned to two new recruits to help him break the deadlock. On 7 May, the club announced that Peter Swales, who had already been sitting in on board meetings, was now offically a director. He was joined on the board by Rueben Harris, the assistant managing director of Britain’s biggest retailer, Great Universal Stores, who was renowned as a “fearsome negotiator”. Each had been given ten shares (0.5%).

It appears that Swales’ involvement had begun in late 1970, when he had taken part in informal discussions with City vice-chairman Sidney Rose and director John Humphreys. According to newspaper reports, a tentative agreement had been worked out in April. On 23 June, Swales and Alexander met with consortium members Joe Smith and Ian Niven at the Midland Hotel in Manchester, where the deal was finalised.

The sale of Frank Johnson’s 25% stake to Smith would now go through. Alexander would remain as chairman and would be joined on the board by Smith and fellow consortium member, Simon Cussons. Johnson would also remain as a director, but would donate ‘some of the money’ from the share sale to the club to help with legal costs.

“Joe Smith and his group are now interested in working in harmony with the existing directors for the good of Manchester City,” Swales declared following the meeting. According to the Manchester Evening News,

‘Not only is the power struggle over, but fresh drive and ideas may be injected into the club by the new men.’

The following day the paper hailed the deal as a personal triumph for Swales, ‘the peace-maker who brought the two sides together’ and ‘brilliantly stopped the feuding’. But as with most protracted High Court battles, it was the mounting legal bills and fear of defeat that brought about an agreement. As Alexander’s lawyers no doubt informed him, the 1964 covenant had been built on shaky legal ground.

At an Extraordinary General Meeting on 19 July, a resolution by Swales to change the club’s Articles of Association to allow the number of directors to increase from seven to nine was adopted. Smith and Cussons were then elected to the board. Eight days later the club withdrew the two injunctions it had taken out against Johnson that prevented him exercising the voting rights on his shares.

Manchester City’s board & shareholdings, July 1971

Although the takeover group only had two of the nine board votes, they now controlled the majority to the club’s shares. It meant that if they didn’t get their way on important issues they could force a vote of no-confidence in the board. And the issue that was of most importance to them was the promotion of Malcolm Allison, described by Smith as the “greatest man in football”.

Allison, who had just returned from a two-month suspension from football for calling a referee a “homer”, knew that his time had come. The man who was now being referred to as “Big Mal” in the newspapers was no longer prepared to accept the role of assistant manager. In September he told Shoot! magazine that he wanted the job of Scotland manager. “Scotland is a situation that appeals to me because the potential of their players is so huge,” he declared. “It is my ambition to coach a national team in the World Cup finals in Germany in 1974.”

But there was only one job Allison was actually interested in: Joe Mercer’s.

On 5 October, Alexander issued a statement denying a boardroom rift had developed over the issue. It read:

“Contrary to suggestions, the Board of Manchester City are not at variance concerning Mr. Mercer or Mr. Allison or in fact over any other matter of club policy or direction.”

At a board meeting two days later, Allison was appointed manager. Mercer was given the role of “general manager”. It was a deliberately vague title, but Allison left no doubt about who was now in charge, declaring,

“This means I am responsible solely to the board for the team. I only have to answer to the board. It is nice to have the additional status.”

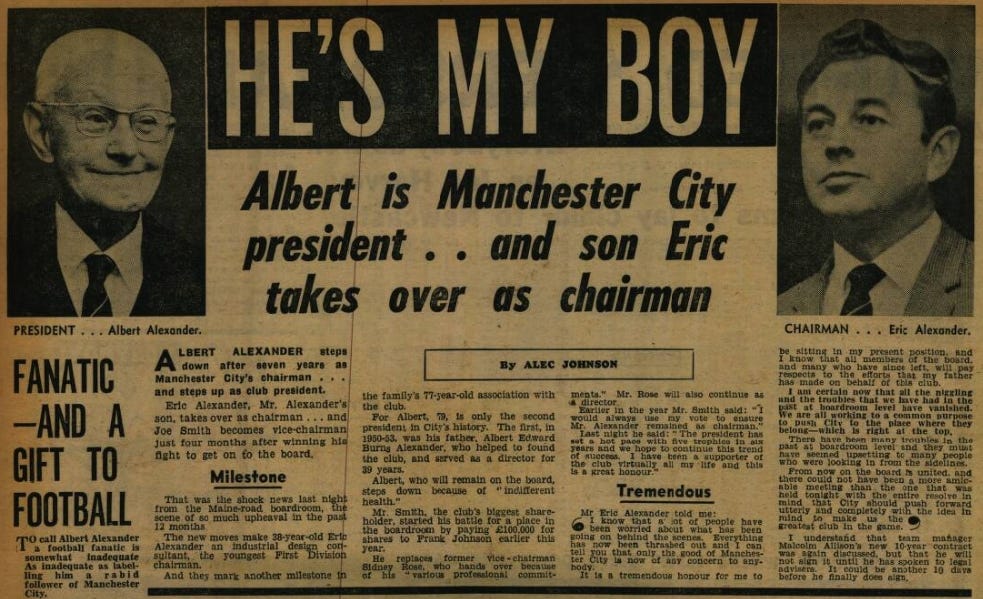

A month later, another wise old head was promoted to a non-job. Now suffering from “indifferent health”, Albert Alexander was appointed club president. He was replaced as chairman by his 38-year-old son, Eric. The change, which also saw Smith replace Sidney Rose as vice-chairman, had most probably been agreed at the Midland Hotel meeting in June.

For City’s new chairman, blue skies now lay ahead. He told the Daily Mirror,

I am certain now that all the niggling and the troubles that we have had in the past at boardroom level have vanished. We are all working to a common purpose to push City to the place where they belong—which is right at the top.

From now on the board is united, and there could not have been a more amicable meeting than the one that was held tonight with the entire resolve in mind that City should push forwards utterly and completely with the idea in mind to make us the greatest club in the game.”

Two weeks later the board approved the offer of a ten-year contract for Allison, worth a reported £15,000 to £20,000 a year. City had been on a winning streak since Allison’s promotion. On 11 December they moved into second place following their 4-0 win over Ipswich at Maine Road.

Allison had won the Bell’s Manager of the Month award for November. While the £100 prize money was no doubt welcome for a man of his spending habits, the additional award of a gallon of whisky was the last thing the alcoholic Allison needed.

His relationship with Mercer had now reached breaking point. Following a friendly in Valletta, Malta, on 15 December the two had a blazing row in front of shocked players and directors. According to eye-witness accounts, Mercer told Allison that he had rescued him from the “scrapheap” when he brought him to City. Allison hit back by telling Mercer he wouldn’t have won anything without him.

For most City fans, the “holy trinity” of Bell, Summerbee and Lee—soon to be immortalised in statue form—is the embodiment of the club’s last golden age. But it was another magical “trinity” that had provided the foundations for that success.

Mercer’s contract was due to expire in the summer. And with Albert Alexander’s health rapidly deteriorating, the club was about to lose its two wisest heads.

City’s golden age was now nearing its end.

Part 6